Overcoming anchoring bias key to advisers amid volatility

To be a successful financial adviser, especially during times of peak volatility, it pays to understand and master the human cognitive biases that can often lead to poor decision-making. No doubt the recent share market rout has caused many investors to make poor decisions as a result of taking shortcuts or by being overconfident or oversimplifying a complex decision.

As a financial adviser, making the right decision matters. Not just for your client’s investment returns but for your confidence as well. Knowing your cognitive biases can therefore lead to better decision-making, lower risk and enhanced investment returns for your clients.

There are ten key cognitive human biases of which to be wary:

- Anchoring bias

- Confirmation bias

- Information bias

- Loss aversion bias

- Incentive-caused bias

- Oversimplification bias

- Harry Hindsight bias

- Bandwagon bias

- Restraint bias

- Neglect of probability bias

What is anchoring?

According to the Decisionlab, “An anchoring bias is a cognitive bias that causes us to rely too heavily on the first piece of information we are given about a topic. When we are setting plans or making estimates about something, we interpret newer information from the reference point of our anchor, instead of seeing it objectively. This can skew our judgment and prevent us from updating our plans or predictions as much as we should.”

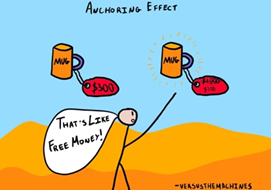

For example, looking at the picture above, the price tag on a mug says the original price was $1,000 but the mug is now marked down by 70%, it’s hard not to think you’re getting a bargain. This conclusion is flawed, however, because the original price is artificial and can be set to anything.

The actual price is $300. Not $1,000.

But who wants to buy a $300 mug, when you could instead buy a $1,000 mug that’s on sale for 70% off? Both are the same. Yet most people want to feel like they’re getting a bargain. That’s anchoring.

And people love to do it.

How does that relate to the finance world?

Anchoring occurs when a financial adviser or their client is anchored to a preconceived price without that price having any intrinsic value. Anchoring bias causes investors to look at the past share price of a company and assume that it will continue to remain so in the future.

For instance, property in Australia has always risen in value over the long term, and performed very well for investors. This has led investors to anchor their housing valuations to the past, ignoring the low-interest-rate environment that prevailed until very recently. In a rising interest rate environment, there is no reason for the real estate sector to boom, and property prices could fall. Investors may be anchored to its past performance and may not sell, despite a housing collapse.

Anchoring biases cause financial advisers to delay selling their client’s investments.

Bitcoin is another good example. Investors can often hold on to a price, say a Bitcoin price of US$50,000, and convince themselves that that’s what BTC is “worth” — because it once traded at that level — even though the market value is now $40,000. An investor so convinced will keep on holding even if it takes a decade to get back to $50,000. The investor gets stuck on the price and will only get mental satisfaction when that $50,000 price is realised.

This anchoring bias is hard to break. Even when new information is released, such as an earnings downgrade, we are often sceptical about downgrading the share price because we are anchored to a higher price based on the past investment performance of the company.

How to overcome this anchoring bias

The reason we anchor is that our minds tend to form shortcuts. To value a stock, in our mind, we find an approximate value and then anchor it.

So, the best way to stop this from happening is to stop using shortcuts.

Instead of valuing a company based on a past price, value a company on due diligence and future earnings. Look forward instead of backward. Understand the company’s current earnings and projected earnings. Consider the outlook statements and broker valuations. Analyse the macro factors that affect the share price now and in the future. When markets are in a boom phase, share prices are generally valued higher than during a share market sell-off.

It’s also handy to know that investors are irrational. Good companies get caught-up in a market sell-off and are often undervalued despite having growing earnings. In the current environment, these are opportunities to look out for.

The bottom line is that financial advisers need to be aware of the possibility that they may be irrationally anchored to a price based on a biased piece of information, which can lead to making a bad decision. Anchoring bias happens subconsciously, which makes it even more frustrating. And sometimes taking the time in making a decision, can make the anchoring effect stronger. The best strategy is to come up with an argument against the anchor price or consider alternative options to aid decision-making. When valuing a company, look forward at its projected earnings, instead of backward. By considering these alternatives, it might be possible to reduce the influence of an anchor.