Bonds are dead. Long live bonds!

Quantitative easing, negative interest rates, and modern monetary theory (MMT) have all but forced the end of the 30-year bull market in government bonds; or have they? As we enter 2021 the chorus of commentators warning of significant capital losses on long-term bond investments and the reducing diversification benefits of that holding continues to grow. But according to Darling Macro, a Sydney-based liquid alternatives strategy, the bell may have been rung too soon.

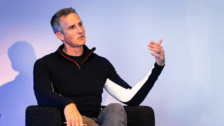

Portfolio manager Mark Beardow, who previously led the global equities team at AMP Capital, is clear when he states that “traditional balanced fund allocations are going to face struggles that include breakdowns of traditional correlations,” also noting that this is likely to occur at a time when even equity markets are displaying ‘duration’ or interest rate risk in their valuations.

The over-riding story of 2020 will no doubt be the boom in alternative investment options. Ranging from private credit to real assets, long-short strategies and even venture capital, advisers have been forced to think outside the square in the search for returns. And why not? According to Beardow, “declining yields and volatility both further dilute bonds’ ability to diversify equity weakness.” Yet at 2020’s most difficult point, in the middle of the March carnage, duration once again proved the saviour for traditional balanced portfolios.

The reduction of interest rate duration in portfolios was a common theme in 2020, with lower interest payments, rising inflation risks and limited diversification benefits exacerbated in a bull market environment. But according to the team it may be too early to de-allocate away from bonds as a short-term equity diversifier, with the yield curve control being used by central banks actually supporting rather than reversing correlation benefits. They compare the benefit of government bonds in a “yield curve control” environment to private debt and similar assets like real estate, noting that the aim is effective to avoid “devastating losses” associated with higher risk investments, but having to accept “minimal capital movement” in the short term.

On the current sellers of bonds, the response is fairly straightforward. Monetary policy and with it yield curve control will remain one of, if not the most important, part of central bank policy in the years to come. Most global central banks have been clear: rates are not going anywhere. While inflation may be the topic du jour, central banks have failed to achieve this outside of equity markets despite an entire decade of quantitative easing and money-printing policies. In fact, the growing likelihood is that inflation is sourced from supply issues, not demand in a post-pandemic environment.

As every asset owner, adviser or investor sat down at the end of the year they were no doubt plotting a course for 2021 and beyond. But where do you start? According to Beardow, those relying solely on a strategic asset allocation or passive, set-and-forget approach to investing, reliant on mean reversion and expecting to be rewarded for the additional risk, may get an unexpected surprise in the years ahead. Darling Macro expects correlation between bonds, equities, and alternatives to actively deviate, which may result in an increasing number of “unanticipated and unmanaged” drawdowns at the worst possible time. The solution, it seems, relies on active risk and portfolio management and a keen eye on the breakdown of correlation relationships.