What makes an ideal entry point for a high-conviction investment team?

For high conviction investors Claremont Global, an exhortation to “own the world’s best businesses” is one they’ve been able to hang their hat on for a decade.

Behind the simple premise, however, lies an almost unquantifiable amount of research that goes into deciding when to buy into a company. As it turns out, reaping a sustainable return from owning the world’s best businesses is an extraordinarily precise endeavour.

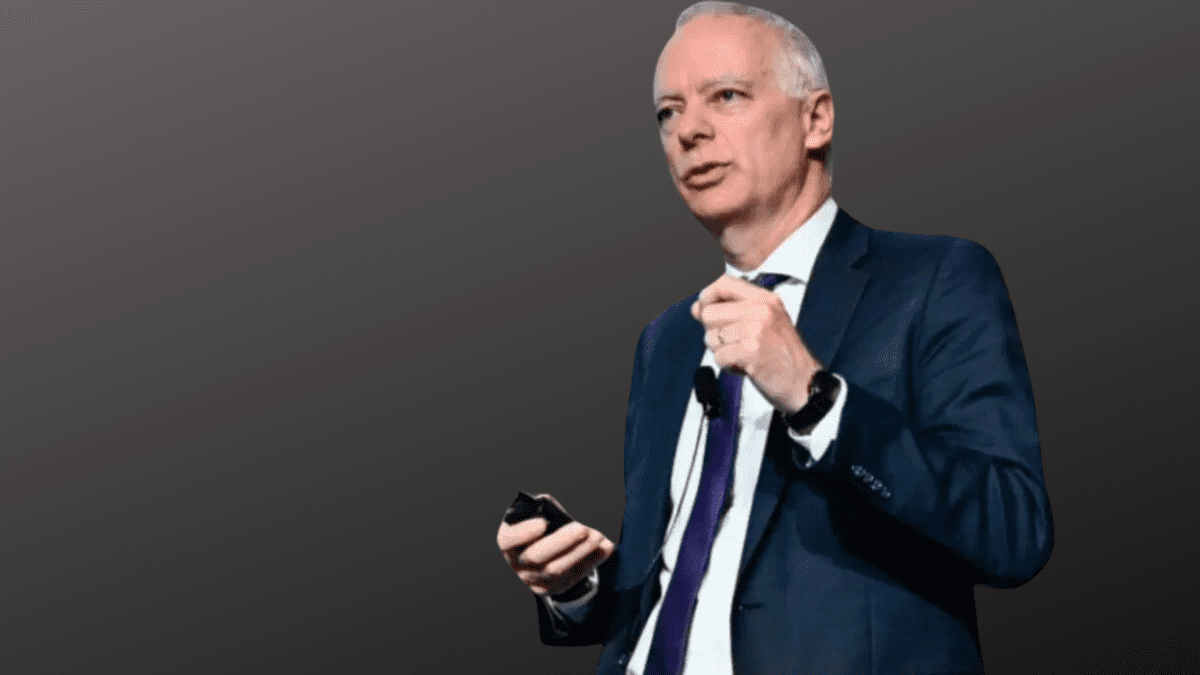

According to portfolio manager Bob Desmond (pictured, left), one of the keys to achieving the complicated is to keep it simple. When assessing companies for inclusion in the Claremont Global Fund, for example, the team maintains a rigid filter that’s patiently applied and seeks to eliminate as many unknowns as possible.

“We exclude large parts of the market where we have to forecast interest rates, commodity prices, the next product lifestyle, or what regulators are going to do,” Desmond said in a recent Q&A with Value Investor Insight. “The future is uncertain enough without complicating what you have to get right.”

A potential company may pass through the initial filters, but for a high conviction team to enter the market the share price needs to become suitably attractive. The relative worth of the investment will always be pegged to its initial entry point. What prompts that entry point, however, can vary.

“Sometimes it’s as simple as a missed quarter or an adjustment in near-term guidance. More often than not a story develops around the business or the macro, or there’s an exogenous event,” the portfolio manager explained. “For Visa, it was during the fintech bubble in Covid when people were selling the stock as if the company was a dinosaur even through it was still growing at mid-teen rates.

“For LMVH it was when Russia invaded Ukraine and the stock sold off heavily even though Russia as a very small part of the business,” he continued. “For Nike it was when China was pushing a boycott of Western brands. Tech shares selling off sharply in 2022 gave us the entry point into Adobe. When interest rates were going up again, that gave us the entry point to CME Group. If we’ve done our work on companies we want to own, we know our entry price and just wait for it.”

When it comes to marking that desired entry point, Desmond says the preferred approach, “which may not win any business-school awards”, is to put a multiple on forecasted five-year earnings and then discount that five-year terminal value back to the present at a discount rate of 8 per cent. “We try then to buy at a 20 per cent or more discount to that value, which gives us the entry point.”

According to Desmond’s fellow portfolio manager at Claremont Global, Adam Chandler (pictured, right), finding the entry point is not as simple as waiting for a company to become cheap. It has to be a quality company with fundamentals that align with a variety of metrics set down by the investor.

“What we’re trying to do is own much better than average companies at valuations that are often at a premium to the market, but not as much of a premium as had typically been the case,” Chandler said.

There aren’t many companies that get through Claremont’s filters and meet the entry point thresholds, but that’s the point of high conviction investing. The team never owns more than 15 companies at a time. It’s also why the firm has managed to earn an annualised return of 14.7 per cent (compared to 12.1 per cent for the MSCI All Country World Index) and built assets under management to $1.5 billion. They’re experts at being careful, and executing precisely.

In today’s market, where indices in developed markets are at or near all-time highs, Desmond says the “wish list” of companies is even shorter than usual.

“That tends to happen when markets have been running like they have,” he said. “You have to be very selective in this market about the companies you’re willing to buy and the prices you’re willing to pay. I certainly wouldn’t be buying an index fund at the moment.”