Tailwind for private lending is just beginning: Pallas Capital

Australian CPI numbers were released this week showing a 6.1 per cent increase in consumer prices, the fastest pace in 30 years. A combination of higher petrol prices, as well as continued rising food, housing, and energy costs, remain the key drivers of the increase. The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) is tipped to raise the cash rate by a further 50 basis-points: predictions are for a rate hike every month until the end of the year.

Either way, rates are rising, and inflation is eroding asset prices and future returns. As a result, investors are realigning their portfolios to increase exposure to energy, inflation-linked bonds, commodities and floating-rate debt.

A niche area that has the potential to benefit from, rather than be impacted by rising interest rates, is commercial real estate (CRE) debt. This was a focus of Craig Bannister, co-founder of specialist lender Pallas Capital, when speaking to financial advisers at The Inside Network’s recent Income and Defensive Asset Symposium.

Following the Banking Royal Commission, banks were forced to tighten lending regulations and hold more capital, creating a gap in the lending market. Non-bank lenders such as Pallas, stepped in to fill the gap. This asset class is among the fastest-growing in the country but remains relatively small in Australia compared to other developed market economies.

“Today, the Australian CRE debt market is a $400 billion market tipped to hit $500 billion over the next few years, with banks now representing 95 per cent of that market versus 5 per cent for the non-banks. With the global average being 35 to 50 per cent for non-bank lenders, Australia certainly has some catching-up to do,” says Reuban Sivarajasingam of Pallas Capital.

When Pallas talks about the opportunity that exists for non-bank lenders, it highlights the attractive market interest rates for CRE debt across an array of loan types.

A bank construction loan attracts interest rates of around 4.5 to 6.0 per cent per annum whereas a non-bank lender construction loan is able to charge higher rates of around 8.0 to 9.0 per cent, a significant opportunity for those investors willing to ‘become the bank’. The differential between the two is due to a few factors, but is driven primarily by the fact that non-bank lenders are a lot more nimble and efficient, they offer flexible terms, can manage loan-to-value ratios more efficiently and they have much closer relationships with their clients/developers than a bank.

“By utilising institutional capital, it lowers the cost of capital which enables investors to capture a better rate of return with less risk” says Sivarajasingam. It also reduces the amount of time that borrowers are left waiting for loans to be approved, increasing the internal rates of return delivered.

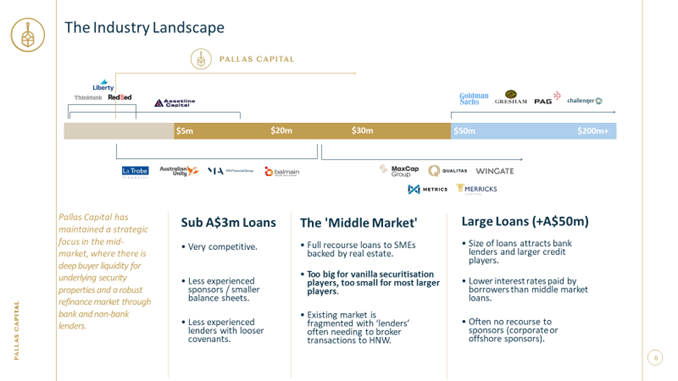

The CRE landscape is made up of a handful of players broken up into three segments, the sub; $3 million loan market is made up of smaller, highly competitive lenders with looser covenants and smaller balance sheets. At the other end of the spectrum are large loans of $50 million or more, where the market is dominated by bank lenders and larger credit players. Lower interest rates tend to be paid by borrowers in this space as they are institutionally backed. The middle market is anywhere between $3 million to $50 million in loan sizes, hosting many competitors offering full-recourse loans to SMEs backed by real estate.

“The CRE debt market has proven to be very resilient over time, with investors historically achieving annual returns of around 8 per cent. That’s a function of rates being lent to borrowers at say 10 per cent under a commercial loan, and investors participating in those loans, receiving a return of around 8 per cent,” says Bannister.

What are the strengths and competitive advantages?

Non-banks like Pallas tend to apply conservative LVRs of less than 65 per cent under first mortgage security and will go to 75 per cent for the second mortgage where deemed appropriate. But valuations are central to the process, with every decision “supported by expert independent valuations. Really this is the key. Get this part wrong and the deal could be mispriced,” says Bannister.

“Property values can fall, as we are now seeing. However, within the 12-month duration of the loan, we are managing the loan to maturity/refinance, but with a buffer of 35 per cent equity in a lot of these loans, we as debt holders do not get impacted. With that 35 per cent equity buffer and a 65 per cent LVR, you can maintain those excellent rates of return to investors,” says Bannister. The benefit being the ability to roll-off and have short-duration loans be repaid, and then re-lent, where appropriate into more attractive opportunities.

Bannister concludes by saying, “The CRE debt market continues to grow strongly at 5.45 per cent a year since 2004, and non-banks continue to win market share, and have been growing consistently by 10% year on year. Given the challenges in the market, private debt managers should be selective on what type of loan opportunities will provide the best risk-adjusted return.”