Ruffer and the art of bubble spotting

Anyone can be taken in by financial bubbles; that’s why they’re so dangerous. It’s also why we at Ruffer believe that navigating bubbles – steering the ship safely past the Charybdis of irrational exuberance – is the most important duty we owe to our clients.

Sir Isaac Newton was one of the greatest scientists in history. He was the Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at the University of Cambridge, President of the Royal Society and even Master of the Royal Mint. His scientific contributions ranged from optics to calculus, but he is best known for founding classical mechanics and for his law of universal gravitation. For all that, Newton lost his life savings in the South Sea Bubble of 1720.

If even the father of modern science couldn’t spot when assets were defying financial gravity, what hope is there for any of us? Fortunately, as we shall see, bubble spotting is as much an art as it is a science, and we can learn many valuable lessons from the experiences of Newton and others down the centuries.

Periods of inflated asset prices have always been a feature of markets. But it was not until December 1720 that Jonathan Swift, the author of Gulliver’s Travels, coined the term ‘bubble’ in a poem dissecting the greed and delusion surrounding the South Sea Company. The metaphor stuck because it was apt: financial bubbles float free of market forces until they burst, and the consequences are messy.

If bubbles are periods when assets become overvalued, it may help to consider what gives an asset value. Typically, assets are valued for their rarity or their usefulness. Gavekal Research distinguishes between ‘jewels’ (rare assets) and ‘tools’ (useful ones). Bubbles emerge when investors either misjudge the scarcity of an asset, such as tulips or gold, or overestimate the future cash flows from new productivity advances, such as the railway or the internet. Some assets, such as property, can be both rare and useful.

The modern definition of financial bubbles is hotly debated. Jeremy Grantham of asset manager GMO takes the scientific approach, asserting “bubbles are definable events when the price action is two standard deviations from a long-term trend”. Robert J Shiller, renowned for challenging the notion of rational markets, calls a bubble “an unsustainable increase in prices brought on by investors’ buying behaviour rather than by genuine, fundamental information about value.”

However bubbles are defined, the problem has always been knowing when you are in one. In seeking to identify them, it helps that bubbles – like the human behaviours which drive them – tend to follow a set pattern, with several distinct phases. We think of those as: national pastime, new paradigm, feedback loops and frauds and scapegoating.

Every bubble attracts more and more new investors until it ultimately becomes a national pastime, with nobody wanting to miss out on the returns everyone else is making. When Joseph P Kennedy, a prominent banker of the Roaring 20s and father of JFK, was given a stock tip by the young New Yorker shining his shoes, he famously decided it was time to cash in his investments, thus deftly avoiding the 90% decline in stock prices which led to the Great Depression.

Not everyone has been equally skilful or fortunate. Charles MacKay was the author of Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds – an 1841 book on crowd psychology and bubbles. Yet even he was sucked into the Railway Mania of the 1840s, when the affluent middle class (created by the Industrial Revolution) crowded into investing in the new railway companies. He famously declared in a newspaper article that “there is no reason whatever to fear a crash”, shortly before the bubble burst.

More recently, we have witnessed the rebirth of retail investing. The number of brokerage account openings has soared new investors have been lured into markets by easy-to-use apps, online forums, and dinner party bragging about profits from day- trading and cryptocurrencies. Some may be tempted to ‘play the bubble’ by investing in the beneficiaries of increased retail trading. But take care: the Uber driver who gives you a hot stock tip may just be the latest incarnation of Joe Kennedy’s shoeshine boy.

All bubbles are based on a new paradigm, which is used to justify high valuations. Some economic innovation, new market or technological advance emerges which, its proponents claim, will change the world for ever, opening up boundless possibilities. Often, there is substance to such claims – but not enough to justify the hyperbole.

For example, over the past two decades, the internet has transformed our lives and the ways businesses operate. But, during the dot.com bubble of the 1990s, stock prices became divorced from reality. The promise was real; it was just the timing and the eventual winners that were hard to predict.

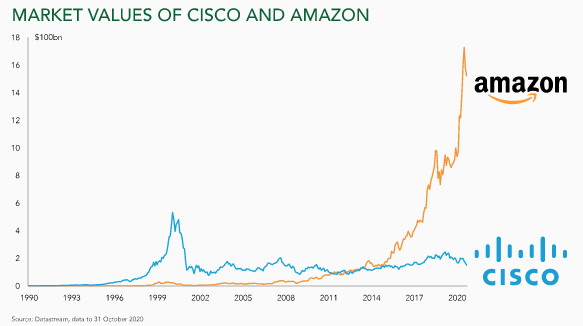

In March 2000, Cisco was briefly the most valuable company in the world. This maker of internet switching gear was one of the expected winners from the build-out of the internet. The logic was that, if you couldn’t predict which dot.com companies would be the winners, surely demand for the kit itself – the picks and shovels to create the infrastructure – would continue to grow. As with other tool-based investment booms, high prices bring forth supply – whether of houses, railways or internet switches – which in the end outpaces demand.

At least Cisco survived. Many of the other hot stocks of the time didn’t. But some – such as Amazon – are now among the world’s most valued companies. Which goes to show that hunting among the debris of bubble fallouts can be fruitful.

As investors make profits, more money is sucked in, allowing the bubble to feed itself, often exacerbated by credit and financial innovation. Ireland, in the run-up to the global financial crisis, was the most egregious example of the global property price boom of the 2000s. At their peak, house prices in Dublin exceeded even those in London.

Financial innovations and slack lending standards in the banking sector (based on the perception that house prices only ever rose) aided the smooth flow of credit during the boom years. That came to a sudden stop when the subprime bubble burst; liquidity evaporated, the global economy slowed dramatically, and house prices crashed.

But this was nothing new. The Dutch Tulip Mania of 1636 was driven by perceived scarcity – it takes a long time for a tulip to grow, so rarer types (the jewels) with distant flowering dates attained the giddiest prices. At the bubble’s peak, one bulb of the rarest tulips cost the same as a beautiful canal- side house in Amsterdam. This bubble was intensified by professional traders, who even created a formal futures market. People began buying tulips through leverage, using margined derivatives contracts. This encouraged the sale and resale of the notes themselves, rather than the bulbs.

The following spring, as new tulips sprouted, it became apparent that supply would soon outstrip demand. The crash was devastating, worsened by those who had bought bulbs on credit, hoping to repay their loans when they sold their bulbs for a profit. Holders of contracts were forced to sell at any price.

After a bubble bursts, frauds are laid bare, and scapegoats are needed so investors can claim they were led astray, rather than greedily chasing profits. Take Bernie Ebbers. As CEO of WorldCom, he embodied the dot.com era, but ended up in jail for fraud after one of the largest accounting scandals in history.

The bursting of the South Sea Bubble also provoked huge public outcry. A full parliamentary enquiry revealed extensive fraud and many scapegoats were publicly shamed. The Chancellor of the Exchequer was even locked up in the Tower of London.

Newton derived his law of gravity after seeing an apple fall from a tree. Likewise, you can only know for sure whether you have been in a bubble “when its bursting confirmed its existence”. Some last a matter of weeks, while others play out over many years. But, because bubbles are based on irrational behaviour rather than underlying fundamentals, it is impossible to time either the inflation or the deflation of a bubble with any accuracy. The great American economist Irving Fisher announced “stock prices have reached what looks like a permanently high plateau” just nine days before the 1929 bull market came to a crashing halt. In contrast, Alan Greenspan made his famous “irrational exuberance” speech on the internet bubble in 1996, four years too early.

Financial history holds important lessons for us today. Even if the common characteristics of past bubbles can help us to identify whether a bubble is inflating, we should not try to time its bursting. At Ruffer, we are careful not to take a single view of how the world might unfold. Given this cautious approach, we avoid fully running with the herd.

Throughout Ruffer’s history, we have assiduously identified and avoided bubbles. The art is to judge when the probability of being in a bubble has risen and position portfolios accordingly. In April 1998, Jonathan Ruffer published ‘One man’s view of a mania’, explaining why we were defensively positioned before the internet bust. We turned similarly cautious in 2006, due to our concerns about imbalances in the financial system. Because of this caution, our performance often lags the market before these inflection points, which calls for the patience and trust of our clients.

We believe in holding a diverse portfolio of assets which should provide protection against the next bubble bursting, without having to know what exactly will happen, or when. The portfolio is unconstrained and flexible, so we can move quickly depending on what we see.