Higher-for-longer no longer, but that doesn’t mean lower-for-longer is in play

US Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell’s recent decision to double-dip on a monster 50 basis-point rate cut shocked the world, with the move typically reserved for emergency economic scenarios like the pandemic or the Global Financial Crisis.

While pundits continue to prognosticate about Powell’s motive, what’s clear is that the inflationary environment has eased enough, in the US at least, for the Fed to indicate that the tipping point has been reached and maintaining higher rates will now do more harm than good. And with that, the higher-for-longer song economists have been singing has suddenly become muted.

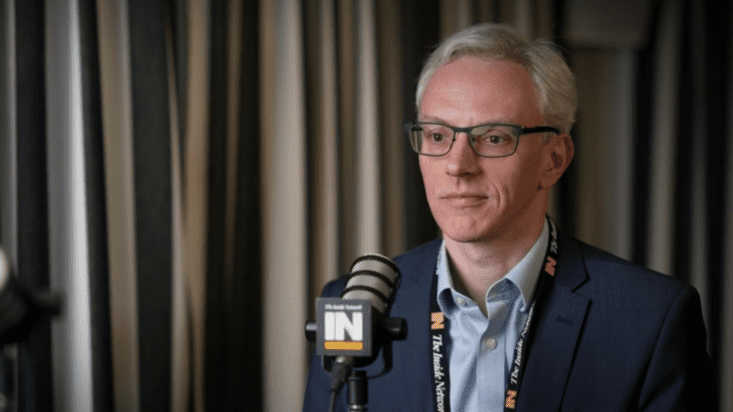

According to Paul Saliba, head of equities and fixed income at SQM Research, the higher-for-longer era in this rate cycle is over. But that doesn’t mean we’ll swing wildly back to ultra low rates.

“Unless there is a resurgence in inflation, high interest rates are not here for long,” Saliba tells The Inside Adviser. “However, it will eventually settle higher than the rate that we all became accustomed to prior to the pandemic – those [ultra-low] rates are unlikely to be revisited, unless there is some severe economic weakness, which would more than likely be predicated by an economic crisis.”

Why Powell went for a double-dip on the guide rate at the world’s most important reserve bank, sans the presence of a significant economic event that would typically predicate it, remains a mystery. The language he used to explain the move was relatively open-ended, but Saliba believes the move may have been a case of playing catch-up.

“The argument to bring rates down to a neutral setting has some challenges; given the Fed is targeting rates to come down to 2.9 per cent, the new rate of 4.75 per cent to 5 per cent is still very restrictive,” Saliba says. “It seems that the 50 basis points cut was likely impacted by the decision to hold rates at the prior meeting and the number of jobs being created in the economy being well down.

“They probably have some concerns that they simply don’t want to express, and are using the language around the rate cut as a tool to manage market response as best they can, whilst taking the action that is likely needed,” he continues. “The dissention seen does indicate that even withing the Fed there are quite meaningful differences opinion which only makes it more clear that they really are working on best endeavours and it is not clear what is required.”

The Fed’s decision will put a degree of pressure on the Reserve Bank of Australia to lower rates in kind, but there shouldn’t be the same degree of urgency because the two nations are sitting at different spots in the economic cycle and dealing with disparate challenges.

“I think the RBA has very different economic conditions to deal with, largely in areas where rates have less impact,” Saliba says. “The consumer is really struggling with cost of living pressures, weak real incomes and now a weaking labour market. Risk of recession based on these factors seems elevated.”