Green energy revolution powering a new commodity super cycle

A new commodities super-cycle is underway, with price increases starting to resemble the resources boom that took place during the mid-2000s. During this time, the prices for commodities used for steel and energy production i.e. iron ore, coal and natural gas, skyrocketed. Global demand for these commodities rose sharply and so did prices. The increase in demand was primarily due to the rapid urbanisation and industrialisation in China which required huge increases in bulk commodities to aid construction.

The commodities boom that is currently unfolding, is the global digitisation and green energy revolution, which may well be even more powerful.

With the onset of COVID-19 and the lockdowns that followed, the move to digitisation became one of necessity rather than choice. Traditional bricks-and-mortar retailers shifted online, triggering a frenzy of buy-now, pay-later (BNPL) vendors offering solutions to eventually replace physical cash. And quietly working in the background is the backbone supporting this transition – the development of 5G and a long list of technological advancements that come with it.

Joe Biden’s victory was a big win for renewable energy and electric vehicles due to his pledge to spend US$2 trillion (US$2.6 trillion) to combat climate change. This gave the EV/battery materials space a big leg-up, helping drive prices higher. There is a long list of Australian lithium, nickel and graphite miners that are riding the back of this boom, because most of the Australian-mined minerals are essential in many green technologies, from solar panels to wind turbines, not just batteries.

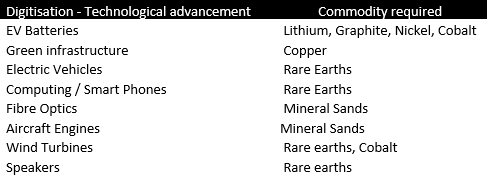

Rare earths (which are not really that rare) are predominantly produced by China. Australia’s Lynas Corporation (ASX: LYC) is currently the only non-Chinese commercial producer of separated rare earths products, and recently struck an agreement with the US government to build a rare earths separation plant in Texas. The rare earth elements include neodymium and praseodymium – Lynas’ major product is NdPr oxide – along with cerium, lanthanum, dysprosium, terbium and erbium, and have a very broad range of potential uses in electric vehicles and green technologies, as well as fast-growing areas such as robotics, medical devices and consumer electronics. And just as important for the US – in defence applications.

Lynas has led the way in Australian rare earths production, from its Mt. Weld mine in Western Australia, which is one of the world’s highest-grade rare earth deposits, but other players are starting to emerge to help loosen the dominance China has on the rare earths market. Other ASX-listed companies working to develop rare earths deposits toward production include Northern Minerals (ASX: NTU), Arafura Resources (ASX: ARU), Australian Strategic Materials (ASX: ASM), RareX (ASX: REE) and Greenland Minerals (GGG).

Australia is also the biggest producer of mineral sands, which include titanium, zircon, rutile and ilmenite. These elements are used in the production of fibre optics, aircraft engines and pharmaceuticals. Iluka Resources (ASX: ILU) is the heavyweight in this field, being the world’s largest producer of zircon and titanium dioxide-derived rutile and synthetic rutile. Interestingly, last year ILU began shipping a rare-earths concentrate containing neodymium, praseodymium, dysprosium, terbium, cerium and lanthanum from its mothballed Eneabba mine in WA.

On the bulk commodity side, copper is the backbone of the EV revolution used in charging stations and in the electrical grid. Major Australian copper producers include BHP (ASX: BHP), OZ Minerals (ASX: OZL), Sandfire Resources (ASX: SFR) and IGO (ASX: IGO).

In a nutshell, the above table outlines the main minerals involved in the next commodity boom. And that fails to include iron ore, which is a key component of the steel required to revolutionise and decarbonise huge parts of the global economy. Interestingly, and positively for Australia, the green energy revolution may well be powered by so-called ‘dirty’ commodities.