Buffet’s ‘not-so-secret-weapon’ is a double-edged sword

Writing in Berkshire Hathaway’s annual letter, pored over by more than three million investors around the world, Warren Buffet warned that markets now look more like casinos than they did when he was a (relatively) young, wide-eyed investor, and that more and more everyday investors are entering that casino in the hopes of winning big.

Markets could still be seized by the same mania that gripped them in 1914 and 2001 (a phenomenon that would be accelerated by the “wonders of technology”), which could leave the stocks and bonds of fundamentally good businesses significantly mispriced.

“Such instant panics won’t happen often – but they will happen,” Buffet writes. “Berkshire’s ability to immediately respond to market seizures with both huge sums and certainty of performance may offer us an occasional large-scale opportunity. Though the stock market is massively larger than it was in our early years, today’s active participants are neither more emotionally stable nor better taught than when I was in school.”

Berkshire can easily handle – and potentially make a return from – financial disasters, Buffet writes, an ability that he dubs its “not-so-secret weapon” stemming from massive earnings and low debt levels. But that ability is also a function of its enormous size, and as Buffet notes himself, later in the letter, “size did (Berkshire) in”.

“If I missed one – and I missed plenty – another always came along. Those days are long behind us.”

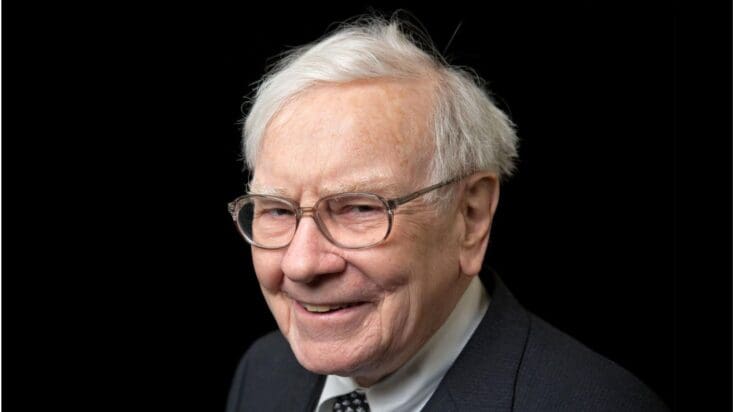

Warren Buffett

On the basis of generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP), Berkshire now occupies six per cent of the universe in which it operates, and doubling its huge base is not possible within – Buffet’s example – a five year period, especially because the company is highly averse to issuing shares.

“There remain only a handful of companies in this country capable of truly moving the needle at Berkshire, and they have been endlessly picked over by us and by others,” Buffet writes. “Some we can value; some we can’t. And, if we can, they have to be attractively priced. Outside the U.S., there are essentially no candidates that are meaningful options for capital deployment at Berkshire. All in all, we have no possibility of eye-popping performance.”

Buffet is by his own admission picky, favouring the rare enterprise that can deploy additional capital at high returns for the future and which is run by “able and trustworthy managers” – the latter a judgement more difficult to make than the former, and which has been the cause for some disappointments at Berkshire.

“This combination of the two necessities I’ve described for acquiring businesses has long been our goal in purchases and, for a while, we had an abundance of candidates to evaluate,” Buffet writes. “If I missed one – and I missed plenty – another always came along. Those days are long behind us.”

What’s in the water in Omaha?

Buffet also showed a softer side in the annual letter, paying tribute to recently deceased business partner Charlie Munger as well as his own sister Bertie, who he called his “perfect mental model” for the group’s shareholder base and “one of the country’s great investors”.

“You may be thinking that she put all of her money in Berkshire and then simply sat on it,” Buffet writes. “But that’s not true. After starting a family in 1956, Bertie was active financially for 20 years: holding bonds, putting one third of her funds in a publicly-held mutual fund and trading stocks with some frequency. Her potential remained unnoticed.

“Then, in 1980, when 46, and independent of any urgings from her brother, Bertie decided to make her move. Retaining only the mutual fund and Berkshire, she made no new trades during the next 43 years. During that period, she became very rich, even after making large philanthropic gifts (think nine figures).”

Buffet, tongue-in-cheek, suggested that something in the air or water might explain the investment proficiency of the inhabitants of Omaha, Nebraska, while crediting Munger as the “architect” of Berkshire Hathaway as it exists today.

“Charlie never sought to take credit for his role as creator but instead let me take the bows and receive the accolades,” Buffet writes. “In a way his relationship with me was part older brother, part loving father. Even when he knew he was right, he gave me the reins, and when I blundered he never – never –reminded me of my mistake.

“In the physical world, great buildings are linked to their architect while those who had poured the concrete or installed the windows are soon forgotten. Berkshire has become a great company. Though I have long been in charge of the construction crew; Charlie should forever be credited with being the architect.”