In search of an inflation hedge

During times of fear, investors often become irrational. As the coronavirus pandemic swept through the globe, fear and uncertainty rose, and investors began selling equities looking for shelter, often parking funds in cash until times were better. The problem with holding cash is its susceptibility to inflation, which erodes its value over time.

During times of economic duress, central banks will use monetary policy that includes cutting interest rates, in the hope of stimulating the economy. In November last year the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) cut rates to 0.10% from 0.25% and combined this with a quantitative easing program of $100 billion, with which it will buy government bonds already on issue. In January this year the US Federal Reserve maintained its target for the federal funds rate at a range of 0%-0.25%: both central banks reiterated that rates will be at these levels for an extended period of time.

Quite simply, interest rates are at historic lows. Increasing interest rates or holding them at historic lows, is bad news for bond-holders. The already low returns that bond holders receive were nudged even lower.

Looking forward, as the RBA starts to print more money to stimulate the economy, the money supply increases, and consumption rises. The increase in monetary demand aims to send wages higher and cause firms to increase prices, so inflation eventually rises, eroding the value of almost every asset. Bond prices fall as the purchasing power of the bonds’ long-term cash flows lose value over time. This makes gold a “safe haven” asset, as it tends to retain its value and has no cashflows. The same thing can be said about most commodities. Often referred to as an inflation hedge, when inflation rises, commodity prices rise as well as they adjust much more rapidly to price pressures and don’t pay out fixed cash flows which erode in value. Most importantly though, commodities tend to be the main beneficiary of those policies which are sending inflation higher, specifically government fiscal spending’s focus on housing construction and infrastructure development.

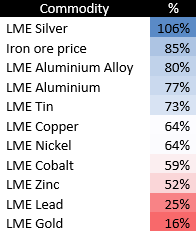

The returns from the major hard commodities are shown in the table below, covering the period from the bottom of the March 2020 crash until today.

While the price moves have been large, these are inherently difficult commodities to which to gain an exposure. Traditionally investors have sought exposure through individual companies, but as 2020 has shown, relying on these so-called “proxies” doesn’t always work. Gold miners are the perfect example, with their share prices tending to suffer in the face of production and hedging issues and not providing the gold bullion price exposure investors are seeking.

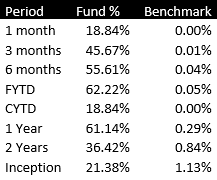

One option into which investors have tapped is specialist managed funds. A great example is the Ausbil Global Resources Fund, a long-short, equity strategy that invests across the entire spectrum. The fund uses a top-down commodity and macro view together with bottom-up stock picking to put together a portfolio of resources stocks that are expected to outperform through the economic cycle. Returns in 2020 are shown in the table below: it’s worth mentioning this occurred with a key commodity, oil, actually moving into negative territory for a time in 2020.

The fund takes advantage of the volatility experienced in the natural resources sector by using a long/short approach to be able to generate positive returns in both rising and falling commodity markets. It achieves this through high-quality “natural resources companies and associated industries, which are expected to have sustainable earnings and free cash flows.”

The Ausbil fund will also short-sell stocks that it thinks have declining earnings/cashflow or commodity-specific headwinds: Ausbil uses short-selling to manage risk and market or commodity exposures.