The race for a COVID-19 vaccine – are we there yet?

Executive summary

Societies and governments around the world are looking at a COVID-19 vaccine as the panacea that will enable the world to recover, reconnect and regain our way of life. Since the genetic code for COVID-19 was unlocked, researchers have set out in an unprecedented and coordinated effort to make a vaccine available on a mass scale.

Today, there are more than 150 vaccines being developed around the world, with many of these in late-stage clinical trials. Governments, industry and philanthropists have injected tens of billions of dollars into the development of vaccines with the aim of accelerating a process that normally takes around 5 to 15 years. Timeframes for achieving a safe, clinically validated and commercially ready COVID-19 vaccine vary but there are several front-runners that aim to have initial doses available within the next several months.

This article provides some information about the virus, a summary of the development process of vaccines and an overview of the companies that are currently leading the race. As the COVID-19 landscape rapidly evolves, we will be publishing periodic updates on the state of play with regards to vaccine development and the global effort to combat the pandemic.

Introduction

COVID-19, also known as SARS-CoV-2, is believed to have originated in China in mid-November 2019. It is the third coronavirus outbreak in the past twenty years after SARS-CoV (severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)) in 2002 and MERS-CoV (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS)) in 2012. The World Health Organisation (WHO) declared a pandemic on 11 March 2020. COVID-19 is an RNA virus, 82% genetically similar to SARS and 50% to MERS. No vaccines were developed for either SARS or MERS due to a number of factors, including technology capabilities at the time, availability of patients (once the disease dissipated) and long-term commercial viability considerations. Although both SARS and MERS were eventually brought under control, COVID-19 is highly contagious. According to the WHO, as at 1 November 2020, there have been 45.95M confirmed cases and 1.19M reported deaths, a fatality rate of 2.6%. Though SARS was much more deadly with a 11% fatality rate, it was not as contagious. One possible explanation for that is that in COVID-19, the viral load (i.e. the amount of the virus) appears to be highest in the nose and throat of people shortly after symptoms develop, whereas with SARS the viral loads peaked much later in the illness. For comparison, COVID-19 is 26 times more deadly than seasonal flu, which has a death rate of 0.1%.

Many countries are still finding their feet and acclimatising to a “COVID normal”. Major drug companies and smaller biotechnology companies are in a race to be among the first to create a safe and validated vaccine, seeking to capitalise on the lucrative opportunity that a successful vaccine offers.

COVID-19 is widely accepted as the most serious public health threat seen in a respiratory virus since the 1918 Spanish Flu. While SARS had an 8-month run and spread to 26 countries, the COVID-19 pandemic is not showing signs of slowing down. Until COVID-19 vaccines are administered on a mass scale, the best that we can hope for is “COVID normal”.

The vaccine development process

It normally takes 5 to 15 years to develop a vaccine. At the start of the pandemic, experts said it would take at least 18 months to have a deployable product (mid 2021), which would be record-pace. Within two weeks of the COVID-19 sequence being made available in late January, scientists developed molecular diagnostics. 15-minute blood tests were fast tracked as point-of-care screening, and there are now (only nine months later) more than 150 vaccine candidates under development, with a number already in human trials.

The development of a vaccine and, more broadly, any drug, is a multi-staged process. The chemical compound being investigated must successfully pass the requirements of the relevant regulatory authority in order to progress to the next stage. Specific requirements vary, but the following stages are generally accepted and used fairly consistently around the world.

Pre-clinical testing: Scientists test a new vaccine initially on cells and then on animals, such as mice, hamsters, dogs or monkeys, to see whether it produces an immune response.

Phase 1 clinical trials: Clinicians give the vaccine to a small number of people (usually less than 100) to test safety and find the right dosage. A Phase 1 trial may also look for early signs that the vaccine stimulates the immune system (i.e. efficacy).

Phase 2 clinical trials: Clinicians give the vaccine to a larger group of participants, usually several hundred people. These clinical trials test whether the vaccine is affecting different groups of people in different ways and further test the vaccine’s safety and effect on the immune system.

Phase 3 clinical trials: Clinicians give the vaccine to thousands of people and wait to see how many become infected, as compared to others who are given a placebo. This is also another opportunity for clinicians to observe rare side effects that were not exhibited in earlier trials. There are multiple COVID-19 vaccines currently in Phase 3 clinical trials, which have between 9,000 and 60,000 participants for each vaccine candidate, spread across many sites around the world.

Combined trials: A common way to accelerate drug development is to combine phases. This has been an especially common strategy for companies developing COVID-19 vaccines, with many vaccines currently in combined Phase 1/2 or 2/3 trials.

Approval: Regulatory review and approval is generally done at the country level, during which regulators review the results of the clinical trials before making a decision. In the US, this function is performed by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), in Europe by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and in Australia by the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA).

In June, the FDA announced that, in order to win regulatory approval, a vaccine would need to prevent the disease, or decrease its severity, in at least 50% of the people who receive it. Though this standard applies to full approvals, the agency did not rule out temporary approvals, called emergency use authorisations (EUAs), which would be assessed on a case-by-case basis and typically based on less stringent requirements. As is relatively standard with all drug approvals, the FDA would require drug companies to monitor the vaccine’s performance after approval for emerging safety problems.

China and Russia have already given early approval to some locally-developed vaccines before the completion of Phase 3 trials. These trials are ongoing and the use of the vaccines is limited, though experts say that the rushed process may pose a serious risk of adverse health consequences.

Vaccines currently in Phase 3 trials

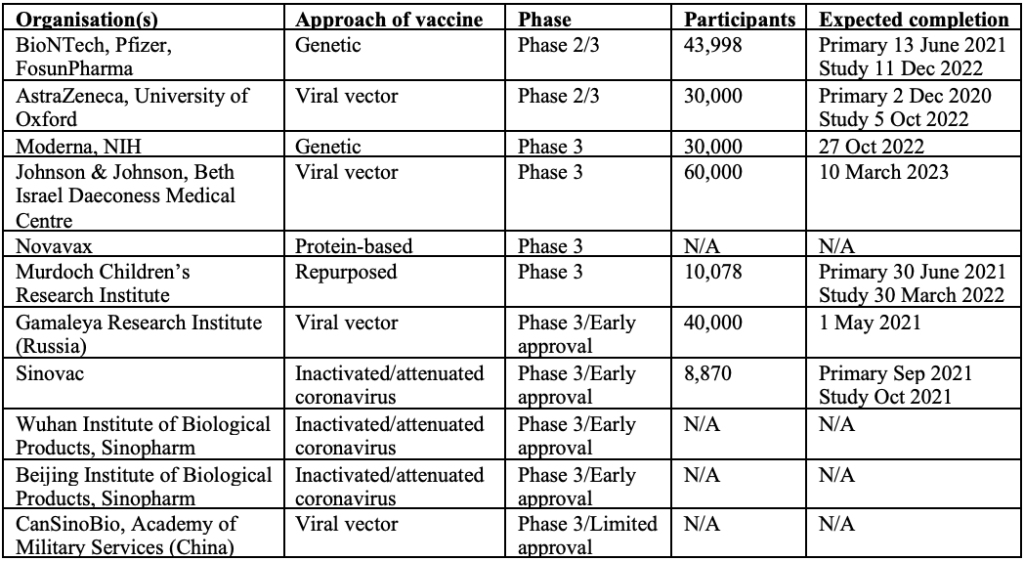

There are currently 11 vaccines in Phase 3 clinical trials. Of these 11 vaccines, 2 are in combined Phase 2/3 trials, 4 are in Phase 3 trials and the remaining 5 are approved for early or limited use while still in Phase 3 trials (4 of which are in China and 1 in Russia). Unfortunately, there is limited publicly available information about the vaccines being developed in China.

In order to get full immune response, most leading vaccine candidates will require 2 doses 28 days apart, other than Pfizer’s, where the second dose is administered 21 days after the first. The first shot would prime the immune system, helping it recognise the virus, and the second shot would strengthen the immune response.

Operation Warp Speed

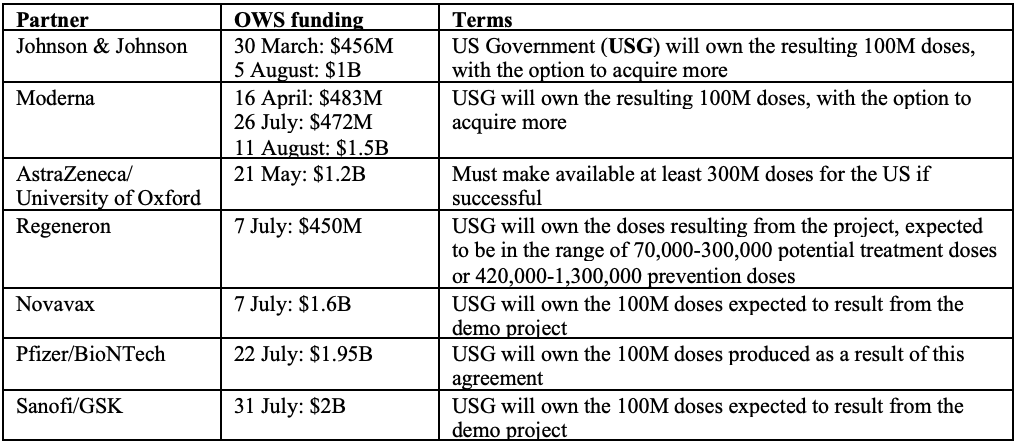

Operation Warp Speed (OWS) is a partnership that includes a number of American organisations – the FDA, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) and the Department of Defence (DoD). The goal of OWS is to produce and deliver 300 million doses of vaccine, with initial doses available by January 2021. The Trump administration hopes that by providing additional funding to those drug manufacturers with leading vaccine candidates, these companies can significantly compress the development timeframe. To date, approximately $10B worth of federal funding has been disbursed under OWS.

Note that the above table only includes funding designated to vaccine development and some (but not all) of the funding designated to manufacturing (where the recipients are Big Pharma). An additional circa $1.5B has been allocated to other US manufacturers who are not Big Pharma and to distributors.

There have been recent claims that the Trump administration has attempted to shape the FDA’s protocols and policies surrounding granting of EUAs to COVID-19 vaccines, with the goal of eliminating a provision that would effectively preclude a vaccine before election day. However, the FDA has stated that it has communicated its new standards directly to drug makers and has made it clear that its requirement for two months of safety data would remain, as would the requirement for an independent panel of experts to assess each vaccine candidate before a final decision is made.

In Europe, the EMA is using “rolling” reviews to significantly fast-track the approval process. This involves assessing data on experimental candidates before all of the evidence needed to make a final decision is available. The EMA has already begun evaluating Pfizer and BioNTech’s candidate, with their Phase 3 trial, expected to recruit between 37,000 – 44,000 participants, having already administered the second dose of the vaccine to more than 28,000 as at the date of this article.

The Australian landscape

In August, the Australian Government signed a letter of intent with AstraZeneca, under which the British pharmaceutical giant would provide 25 million doses of its vaccine, most likely manufactured at the CSL laboratories in Melbourne.

Upon signing of the AstraZeneca letter of intent, CSL commented that the development of its own vaccine in collaboration with the University of Queensland (UQ) remained its immediate priority. Only a few weeks later, the Australian Government signed another agreement with CSL, this time for the supply of 51 million doses of the UQ vaccine, should it prove successful.

The Australian Government has promised citizens that, should either of these clinical trials prove successful, a vaccine would be made available to each Australian free of charge.

A third domestic candidate is being developed by the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute (MCRI). It is currently in a Phase 3 trial involving 10,078 participants. MCRI’s vaccine candidate is a repurposed tuberculosis vaccine, with completion of the study estimated for early 2022.

Broader impact of COVID-19 on the economy

Undoubtedly, the pandemic has had a significant impact on fiscal budgets and capital markets. In April, BCIF wrote an article discussing the effect of COVID-19 on the economy and the key lessons for governments, investors and individuals. We predicted that the healthcare sector would rebound relatively quickly (a prediction that turned out to be correct) and that the virus would highlight the need for more resources to be directed towards healthcare.

Conclusion

There are a lot of observations we can make about the battle against COVID-19. We saw Wall Street suffer its worst week since the GFC in March 2020, governments forced to make tough decisions and prioritise certain demographics over others, unprecedented travel restrictions and citizens largely confined to their homes for weeks or months at a time. We have seen the catastrophic impact that an unlucky string of genetic mutations can have on the world, but also the speed and co-ordination with which the world’s scientific community can spring into action to combat it. Never before have we possessed the knowledge and resources to facilitate such a flow of information, the analysis of so much data and, despite the restrictions on travel, the focusing of the world’s greatest minds on one common goal.

Above all, this pandemic has once again reinforced the importance of health. The desire for ourselves, our families, friends and neighbours to live healthy and long lives is one of a handful of traits shared by every community in the world. This is what pushed the global effort to combat COVID-19 into overdrive. Health will remain a priority long after the pandemic is over.

As the world looks to the health industry for a solution, capital markets have either recovered or are on their way to doing so. We have seen what happens when our health is in jeopardy, and learnt the costs of not being prepared. It is critical that we consider the lessons this pandemic has taught us against our core values and priorities and move swiftly to implement necessary changes. Once COVID-19 has been brought under control, the most important thing that governments, investors and individuals can do to avoid a repeat is to support the industry that we quite literally cannot live without – healthcare.

This article was written and researched by Helen Fisher, from the Bio Capital Impact Fund. Bio Capital Impact Fund (BCIF) is a global evergreen fund, investing into both public and private companies in the healthcare sector.

BCIF has identified the following four key themes that we believe will underpin healthcare over the next decades: Personalised/precision medicine, feeding the world, infection diseases and prolonging health. As priorities begin to shift post-pandemic, we expect to see even more rapid growth across these four areas.