RBA offers excuses on inflation, still insisting it’s temporary

The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) has defended its poor track record in forecasting inflation and says it could not have predicted one-off events and their impact on prices. Despite this admission, Governor Philip Lowe still thinks inflation will be “temporary” and fall back next year, though other economists doubt this.

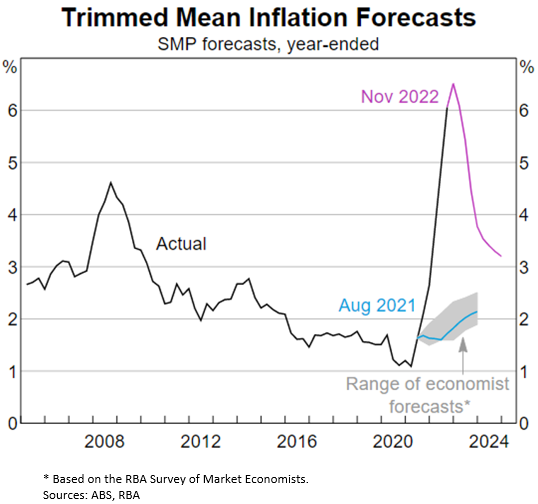

Inflation in advanced economies over the past year has exceeded most central bank forecasts by around 5 to 8 percentage points, according to the RBA’s recent Statement on Monetary Policy. One year ago, most central banks, including the RBA and the US Federal Reserve, said 2021’s price increases would be temporary only. Inflation was seen peaking at around 3.5 per cent in most developed economies.

Yet here it is at almost 8 per cent in Australia, around 10 per cent in Europe and over 8 per cent in the US, the highest levels in decades. Inflation has not been “transitory”, as Lowe (pictured) insisted in late 2021 it would be. But sticking to this view, Lowe recently declared the RBA will “make sure” that the current high rate of inflation is “only temporary.”

In contrast to Lowe’s view that inflation will fall back to below 4 per cent next year, the International Monetary Fund is predicting that inflation “will stay significantly above central bank objectives, at about 6 per cent and 12 per cent, respectively, in advanced and emerging European economies” in the next year.

The chart below from the RBA shows most economists poorly predicted inflation.

RBA couldn’t have predicted one-offs

The RBA defends its performance by saying its economic models were not prepared for one-off events such as the war in Ukraine, the COVID-19 pandemic and the eastern Australia floods.

“As one of the largest economic shocks in a century, the inflationary effects of the pandemic-driven imbalance between supply and demand for goods both globally and domestically played an important role in the forecast miss,” the RBA statement says.

“Other unforecastable shocks – such as the effects of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the Australian east coast floods – also contributed,” the statement says. “The bank’s inflation models (like most forecasting models) underestimated inflation over the past year as it is difficult for forecasting frameworks to capture the signal from unprecedented events.”

The RBA currently forecasts that headline and underlying inflation are both expected to decline to about 3.25 per cent by the end of 2024, from a peak of 8 per cent in the December 2022 quarter and down 4.75 per cent in December 2023. Higher electricity and gas prices are likely to slow the return of inflation to the RBA’s target range.

Stephen Miller, an economist and adviser to GSFM Funds Management, sits comfortably with current RBA inflation forecasts but thinks the central bank has not considered upside risks enough in recent times.

“In particular, the RBA was guilty of failing to indicate the ‘fat tails’ attaching to the distribution of potential inflation outcomes around its central forecasts; in particular of the upside risks, of which it should have been aware given the experience of the 1970s and what any manifestation of those upside risks might imply for monetary policy,” Miller says.

Upside still seen for inflation

Yet whether inflation returns to the RBA’s 2-3 per cent target band remains to be seen, with trimmed mean inflation expected to fall to 3.8 per cent in 2023. “I see significant upside risk to that forecast,” says Miller.

Diana Mousina, senior economist with AMP Australia, agrees with the RBA’s Lowe that some parts of inflation are still temporary and in Australia “we probably have more temporary [inflation] than other countries because of flooding all year impacting fresh food prices.” She expects inflation to come down a bit quicker than the RBA does, with a forecast of 4 per cent over the year to December 2023.

Other economists, however, expect inflation to remain high across developed nations. According to Charles Goodhart, an emeritus professor at the London School of Economics, and Manoj Pradhan, founder of research firm Talking Heads Macro, an inflationary environment will prevail for years to come.

That’s because the availability of labour is expected to remain tight, and dependency ratios worsen as populations age, so “the underlying context will remain inflationary, not disinflationary as the mainstream still believes,” Goodhart and Pradhan write in their publication, Centralbanking.com.

According to the IMF, the big risks are around inflation remaining entrenched, especially in Europe but also in other developed nations. “The pandemic and Russia’s war in Ukraine might have fundamentally altered the inflation process, with rising input and labour shortages contributing notably to the recent high-inflation episode,” the IMF says.

“This suggests there may be less economic slack and, accordingly, more underlying inflationary pressures, than commonly thought,” it adds. “The central banks should continue raising policy rates for now. Real interest rates remain generally accommodative, labour markets are projected to be broadly resilient, inflation forecasts are above target, and inflation is still at risk of further increase.”

In Australia, the labour market is very tight – at 3.5 per cent, it remains around the lowest rate in nearly 50 years. The RBA forecasts the unemployment rate will remain around 3.5 per cent until mid-2023, before rising to around 4.25 per cent by the end of 2024 as economic growth slows.