‘No pain, no gain’: Marks on the investing game of chess

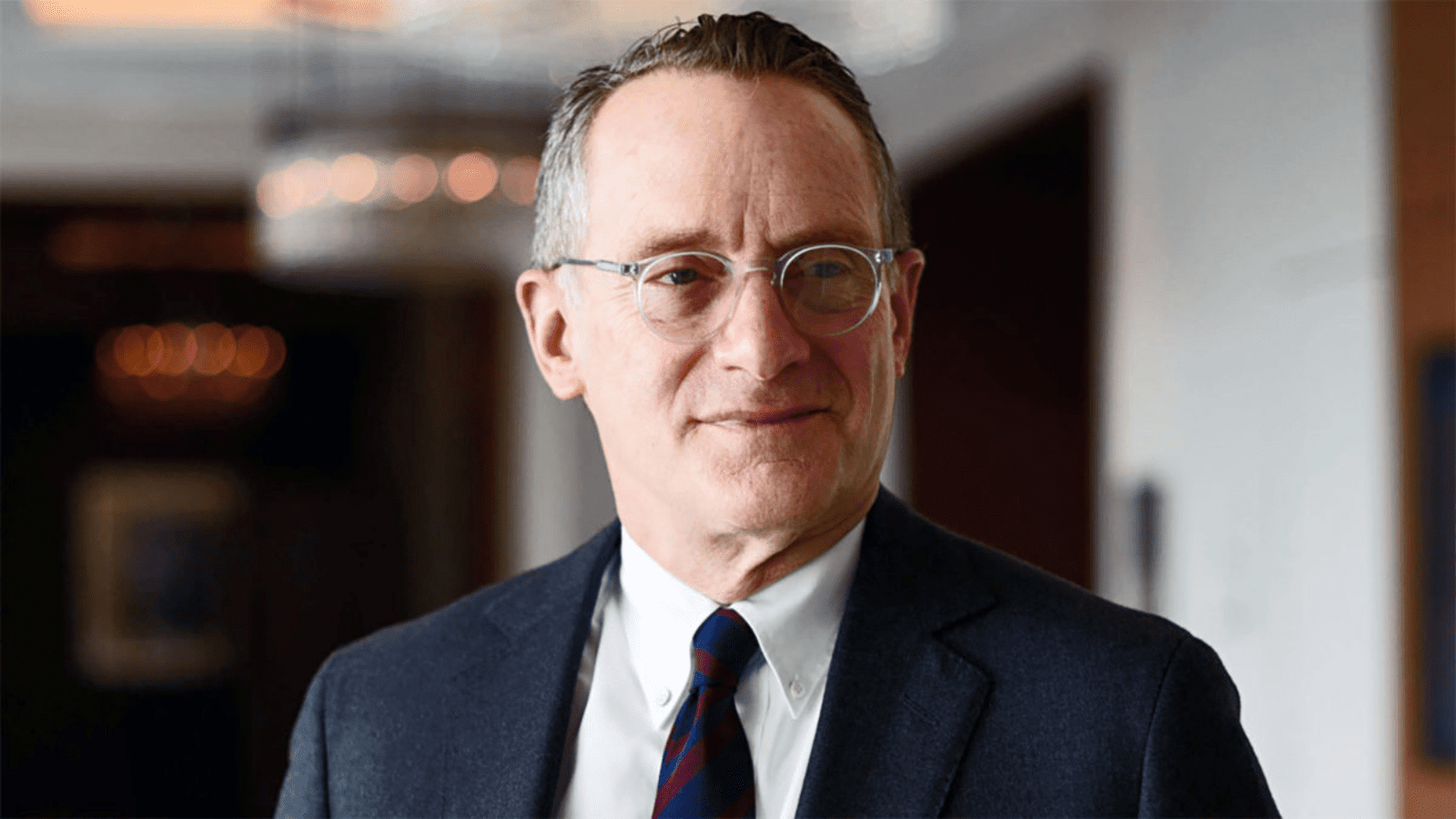

Running to a fairly abbreviated four pages, Howard Marks’ latest memo deals with the “indispensability of risk” – and why investors don’t like taking it.

It stems from his perusal of an article in the Wall Street Journal titled “Chess Teaches the Power of Sacrifice”, which notes that many positions can’t be won without something of value being given way – the aforementioned sacrifice. Some of those sacrifices are “shams”, where it’s easy to see the benefit of giving up a piece; others are “real” sacrifices, where giving up a piece offers gains that are neither “immediate nor tangible”.

In Marks’ analogy, a sham sacrifice is buying a 10-year U.S. Treasury note. You give up the use of the money for 10 years, but that’s only an opportunity cost and brings with it the certainty of interest income. Most other investments are “real” sacrifices – and tough to make.

Because the future is uncertain, investors have to choose between a) avoiding risk and having little or no return; b) taking a modest risk and settling for similarly modest return; or c) taking on a high degree of uncertainty in pursuit of big gains and accepting the possibility of “substantial permanent loss”.

“Most investors are capable of accomplishing ‘a’ and most of ‘b’,” Marks writes. “The challenge in investing lies in the pursuit of some version of “c.” Earning high returns – in absolute terms or relative to other investors in a market – requires that you bear meaningful risk – either the possibility of loss in the pursuit of absolute gain or the possibility of underperformance in the pursuit of outperformance.”

The risk of not taking enough risk is “very real”. Investors might earn a return insufficient to support their cost of living, while big investors might underperform their benchmarks or their stakeholders’ expectations. But they can’t expect to be compensated just for taking it.

“Not every effort will be rewarded with high returns, but hopefully enough will do so to produce success over the long term,” Marks writes. “That success will ultimately be a function of the ratio of winners to losers, and of the magnitude of the losses relative to the gains. But refusal to take risk in this process is unlikely to get you where you want to go.

“You shouldn’t expect to make money without bearing risk, but you shouldn’t expect to make money just for taking risk. You have to sacrifice certainty, but it has to be done skilfully and intelligently, and with emotion under control.”