Expensive assets suffer most when bubbles burst: Orbis Investments

When it comes to stock market bubbles, 2022 was not so bad, at least compared with the bursting of past historical bubbles. On the ‘Buffett indicator’ comparing the value of the stock market to gross domestic product, the ‘everything bubble’ of 2021 was more extreme than any episode in the last half century. Signs of silliness abounded. In echoes of Dutch tulipmania, ‘investors’ in non-fungible tokens paid millions for the rights to freely reproducible digital images. Dogecoin, which was created to mock the silliness of Bitcoin, reached a market value of nearly $60 billion.

The stock market was not spared its share of speculation. Oceans of free money led to a boom in cash-gushing tech firms, cash-torching tech firms, electric vehicle outfits, and any company with the intoxicating whiff of disruptive innovation. Many of those stories started with a kernel of truth, but as Seth Klarman, managing director of hedge fund Baupost Group, puts it, “at the root of all financial bubbles is a good idea carried to excess.”

*Read Orbis Investments’ whitepaper ‘Sunrise on Venus: Investing for the Next Decade’ here.

Anyone with paper to sell took advantage of that excess. Tesla sold $12 billion, or about one Nissan Motor Company, worth of shares. Whatever the motivations of the offsetting buyers, long-term intrinsic value doesn’t seem to have been high on the list – the average Tesla share is bought and sold more than six times a year. 2021 set all-time fundraising records for stocks, corporate bonds, leveraged loans, blank cheque SPACs, private equity funds, venture funds, and crypto assets. Financial promoters became celebrities, and celebrities became financial promoters.

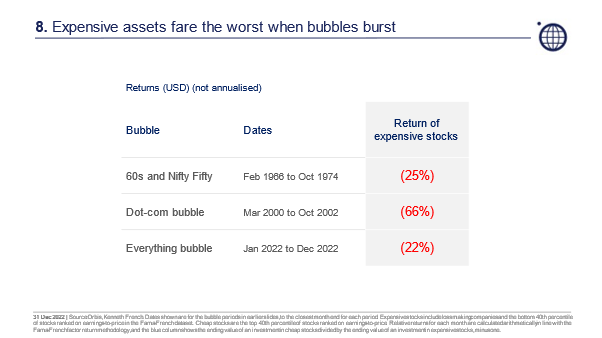

Now that money has a cost again, the craziest assets have crashed the hardest, though they have enjoyed a bounce so far this year. Turning to the more pedestrian stock market, the experience of last year rhymes with history. When stock market bubbles crash, the most expensive assets invariably fare the worst.

A change of leadership

Winners also tend not to persist. In every era, the continued success of the biggest companies seems certain. In 1989, business school students in America rushed to copy the practices of Japanese companies, which were outcompeting their peers everywhere. Concern that Japanese automakers would demolish Detroit led the US government in 1980 to close a loophole in the “chicken tax”, which effectively put a 25 per cent tariff on all imported light trucks. The rule persists to this day, and US automakers have >90 per cent market share in lucrative light truck sales.

In 1999, it seemed inevitable that tech company Cisco Systems, as the enabler of the internet revolution, would grow to the sky. As the West struggled and China ascended in 2007, commodity companies and Chinese enterprises seemed assured of success. Today, it is difficult to imagine a market without the gargantuan growth of Apple, Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon and Meta. Yet over the past 30 years, only Microsoft has managed to stay among the world’s ten largest companies. If the past is a guide, the world’s most valuable companies will be a very different list ten years from now.

This is a unique problem for passive funds, which hold shares in proportion to their market capitalisation. That feature makes indexing a stealth momentum strategy – a huge benefit to passive investors through the persistent trending market of the last decade, but a danger when the trend reverses.

In 2007, when Apple launched the first iPhone, its share price doubled. But the company was much smaller then. With a market cap of $75 billion and a weight of 0.3 per cent in the MSCI World Index, its huge share price gains contributed just 0.3 per cent to passive portfolios’ returns. In 2020, when Apple revolutionised the world by marginally improving the iPhone’s camera, its share price also doubled. But having started the year with a market cap of over $1 trillion and a weight of 3 per cent in the index, this time its rocketing share price added a full 3 per cent to the returns of index funds. The same is true in the other direction. When Exxon fell 20 per cent in 2015 with a 1.2 per cent weight in the Index, it hurt passive investors much more than when it fell 40 per cent in 2020 with a 0.3 per cent weight.

As long as the trending continues, winners keep getting bigger and making greater contributions to index returns, while losers keep getting smaller and detracting less from passive returns. But as the chart Leadership usually changes with each market shift, above shows, this benefit becomes a risk when trends reverse. Massive exposure to Japan was brutal at the start of 1990, as the Japanese market fell by more than half over the next two years. Massive exposure to tech was brutal in March 2000, as the Nasdaq fell over 70 per cent before bottoming. Massive exposure to Chinese state-owned companies looked clever in October 2007, but share prices fell as much as 75 per cent during the global financial crisis. They are still down 45 per cent from their peak today.

The lesson from history is that passive exposure leads to concentrations in expensive areas just before those areas suffer. That is alarming if we consider how passive portfolios have evolved since the global financial crisis.

1 Having been a member of the Dow Jones Industrial Average for 92 years, Exxon was booted out in August 20 tripled since then.

2 This is also why studies show that a tiny number of stocks generate the bulk of long-term stock market returns. That is true – but only for indexes which never actively trade. Sometimes trading, like selling Cisco in 2000, makes sense