The case for investing in the real estate debt sector

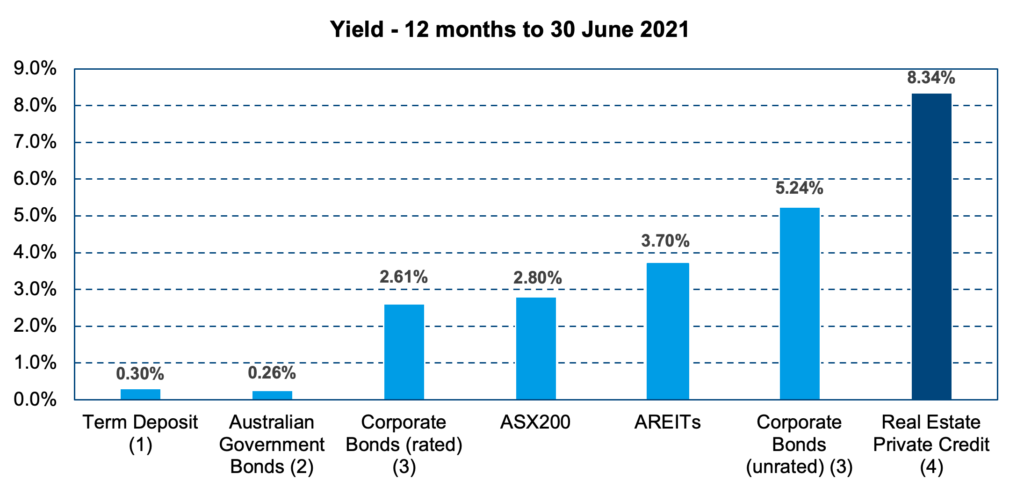

Interest rates and hence yields from most classes of investment, have experienced significant compression. This is true of cash, fixed interest and equities. Elevated listed equity market valuations have further compounded the problem as investors also seek downside protection or at least volatility buffers.

Private debt has the benefit of both, yield, and downside protection.

Private debt, especially debt secured by real estate, has been popular with Australian family offices for several years now and institutional investors more recently. The asset class is now accessible to advisers through retail managed funds, as well as LITs. Many advisers have been unable to access the asset class because it isn’t widely covered by the retail research groups or it isn’t available on the large retail platforms – this is starting to change.

The drivers behind the growing investment in real estate debt

The non-bank finance sector in Australia is relatively small, about 10% of the market, by global standards, where in many comparable jurisdictions the market share is between 20% – 30%.

Global banking regulations have changed and in Australia there is a clear pull back by the banking sector from parts of the real estate market. Non-banks have stepped up to fill this gap. For borrowers, it is no longer just about cost of capital, though it is important, but the speed at which non-bank capital can move and be structured to suit the needs of a borrower or asset owner is difficult for a traditional bank to match. We’re not just seeing this in real estate, but more broadly in the Australian mid-market. Australian businesses are increasingly seeking capital partners outside the large banks.

Banks have primarily reduced their exposure to real estate debt by increasing conditions developers need to jump through to obtain finance. For example, the equity banks require from developers has materially increased, in addition to requiring higher pre-sale debt cover on projects.

What is real estate debt?

Real estate debt is similar to traditional bank debt. The lender, in Alceon’s case this is the fund, provides capital to finance the purchase of a property asset, or the development or redevelopment of a property. In return, the fund (and ultimately investors) receives interest on the loan, which is paid either monthly, quarterly, or capitalised and paid at the end of the loan term. The loan is secured by the underlying real asset.

If the loan is financing the acquisition of land, it is secured against the current or ‘as is‘ value of the property whereas, a construction or redevelopment loan is typically secured against the end value of the project. The end value includes improvements that the loan is being used to finance.

For loans financing residential development land acquisition or construction, the weighted loan-to-value ratio (LVR) for senior secured first mortgages, our area of focus, tends to be between 40% – 65%, and gross interest costs to borrowers between 7% – 12% p.a.

In instances where the purchase of a commercial property is being funded, such as an office building or retail centre, the loan is secured against the market value of the asset and the interest is paid with the underlying asset’s rent. Banks continue to be an active lender to commercial property, so usually non-banks finance commercial assets where LVRs are stretched (>65%) or when an asset is being repositioned.

Where does this fit in investment portfolio

We have observed asset allocators place real estate debt in fixed income portfolios as well as real estate portfolios. That said, there is a continued debate about whether real estate debt represents fixed income or simply another form of real estate.

Given this debate, a number of people have written on this subject. The literature takes a couple of different perspectives from looking at the type of debt to what it is secured against.

Take for instance Maarten van der Spek[1]. In his 2017 paper in the Journal of Accounting, Finance and Business Studies, van der Spek argues that the key factor is the structure of the debt and the place it sits in the capital stack. He contends that senior secured debt is most akin to fixed income given investors receive a fixed or floating return that has no correlation with investor outcomes for the equity component or the underlying real estate. Whereas mezzanine, is more likely to have investor outcomes correlated to real estate equity. van der Spek[2] further observed that as leverage was increased (to 70%), the correlation to equity and real estate increased marginally and naturally, this would seem the logical outcome of instances where senior debt has less equity buffer in the capital stack.

The flipside to van der Spek’s argument is reasonably straight forward – that the underlying asset is real estate, so it should naturally sit within real estate portfolios.

The tightening of cap rates globally in recent years has seen many institutional investors allocate to real estate debt. Given the late stage of the real estate cycle and low interest rate environment, investors allocated capital to more defensive real estate debt strategies where they were happy to cede equity upside for enhanced income and downside protection.

What is the risk profile?

Senior secured first mortgage debt sits at the top of the capital stack. This means it is the first to get paid and the last to lose capital should the underlying asset become impaired.

Alceon primarily focuses on senior secure first mortgage debt with conservative LVRs. Where the underlying property becomes impaired, it would have to fall in value by greater than 35% before investors lost any of their principal because our senior debt LVRs generally range between 40% – 65%.

Real estate debt is generally held to maturity, so held at book value, and not marked to market periodically. Therefore, investors don’t experience a fluctuation in underlying asset values. Where interest isn’t paid on a monthly basis, it is accrued in the net asset value of the portfolio. The accrued interest is paid to investors when the actual interest or cash is received by the fund.

[1] Maarten VDS., ‘Investing in Real Estate Debt: Is it Real Estate or Fixed Income?’ ABACUS, Vol. 53, No.3, 2017

[2] Ibid