Is Team Australia tightening too fast?

When COVID-19 found its way to Australia the health advice was to mandate social distancing by closing businesses deemed non-essential and restricting people’s movement. The economic consequences were tragic – both at the aggregate level and because certain industries and occupations were far more heavily impeded. A broad and bold policy response was required, and this is what our policymakers delivered. Team Australia combined elected officials with appointed technocrats and introduced a range of programs designed to dampen the economic consequences of COVID-19.

Now, roughly 12 months later, we make some early assessments of Team Australia’s performance. Firstly, the combined policy response was admirable for both its size and creativity. Next, and perhaps most importantly, Australia is highly unlikely to experience a depression. Yes, we saw 2 consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth – the definition of a recession – but a depression is different and much worse because it renders large swaths of human and physical capital redundant and cripples the medium-term growth outlook. This is not the case in Australia. And finally, the recovery is not over – the unemployment rate is still too high, inflation is too low, and wages growth is too slow for inflation to converge on the RBA’s target.

We position our portfolios in rates and FX according to growth and inflation dynamics. We consider Australia’s growth and inflation outlook in the context of Team Australia’s policies. The alternative would be to focus on just the RBA’s policies and this confuses a once-in-a-generation health crisis with a garden variety recession.

The unemployment rate isn’t yet in wage inflation territory but its much lower vs. the 2020 peak, so on an ‘RBA-only’ basis it would seem the Bank should begin unwinding the extraordinary monetary stimulus being afforded. We would consider this a major policy mistake. On a ‘Team Australia’ basis, the extraordinary monetary + fiscal stimulus is already being unwound and its mostly happening on the fiscal side. We would hope the powers that be at the RBA have studied Japan’s lost decades closely enough not to contemplate doubling down on the tightening.

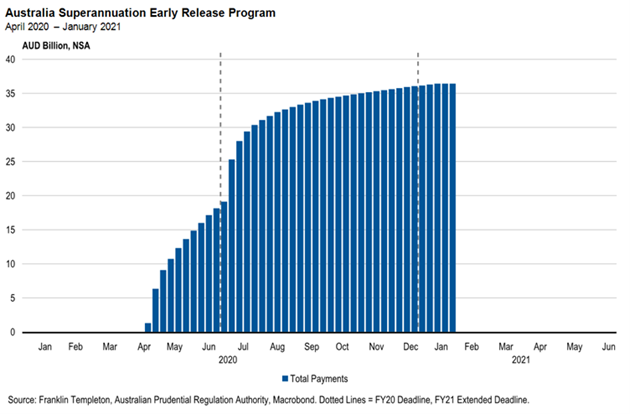

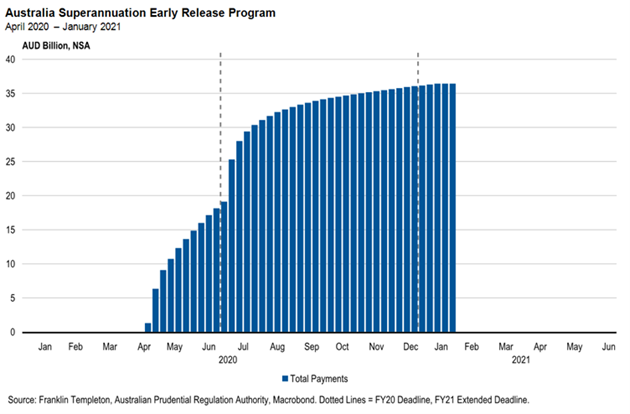

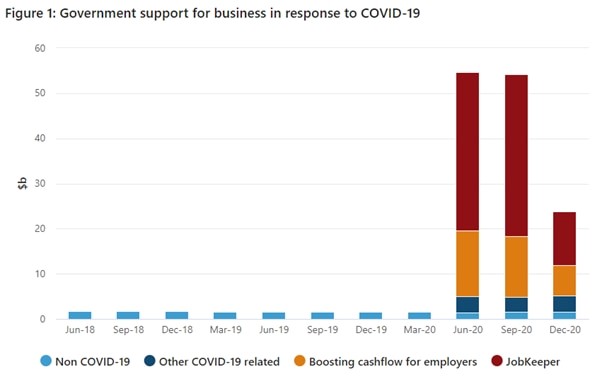

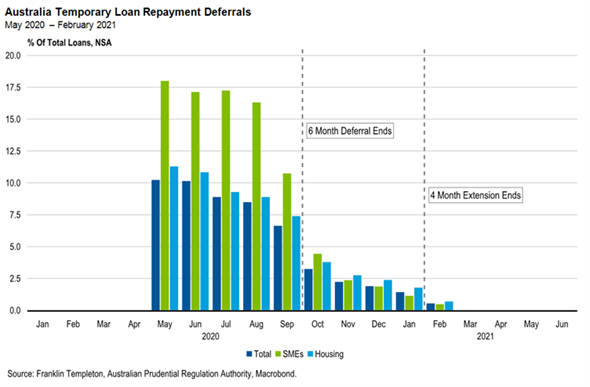

The unwinding of fiscal stimulus is very broad. We show the chronology and caution not to focus too closely on the headline cost of each program because some like HomeBuilder have a much higher multiplier than others like the Superannuation Early Release Scheme. The list also isn’t exhaustive.

The Superannuation Early Release Scheme ended 31st December 2020. Some payments were made in the first several weeks of 2021 but these were for applications made before the deadline. In total approx. $36 billion was paid. The payments aren’t captured as part of GDP growth, but they contribute to the stock of household savings and likely flowed into GDP growth because some of it was spent via household consumption.

Perhaps the two most important stimulus measures were JobKeeper and Boosting Cash Flow For Employers because they backstopped employee wages and business bills, thus preventing a wave of bankruptcies. We crudely use a screenshot from the ABS website to show the evolution of these programs. JobKeeper ended the week finishing 28th March 2021 and tighter eligibility rules which took effect from 28th September 2020 saw payments decline in Q4 2020 relative to prior quarters. We expect to see the same when the final figures through Q1 2021 are released. Boosting Cash Flow For Employers ended after September quarter activity statements were lodged with the ATO. Even allowing for lodgement and processing delays, its likely Q4 2020 marks the last time the ABS will directly incorporate these payments in the GDP figures.

Perhaps the two most important stimulus measures were JobKeeper and Boosting Cash Flow For Employers because they backstopped employee wages and business bills, thus preventing a wave of bankruptcies. We crudely use a screenshot from the ABS website to show the evolution of these programs. JobKeeper ended the week finishing 28th March 2021 and tighter eligibility rules which took effect from 28th September 2020 saw payments decline in Q4 2020 relative to prior quarters. We expect to see the same when the final figures through Q1 2021 are released. Boosting Cash Flow For Employers ended after September quarter activity statements were lodged with the ATO. Even allowing for lodgement and processing delays, its likely Q4 2020 marks the last time the ABS will directly incorporate these payments in the GDP figures.

Temporary Loan Repayment Deferrals was different to other programs because it wasn’t legislated or managed by a public agency. Rather the Australian Banking Association announced the initiative with the support of major lenders. The program was announced in March 2020 and offered 6 month repayment deferrals. In July 2020 the ABA confirmed those able to should resume repayments in September 2020, and a 4 month extension to January 2021 would be offered to those not able to. The program effectively ended in February 2021 though some hardship arrangements likely remain in place.

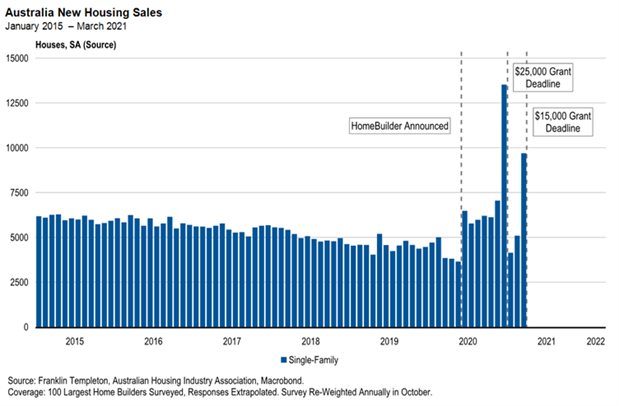

The HomeBuilder program ended 31st March 2021. In the movie Field Of Dreams the whispering voice from above says “if you build it, he will come”. Perhaps The Honourable Josh Frydenberg heard a whispering voice which said “if you subsidise it, they will build”. HomeBuilder was a raging success to the extent it was expected to cost $680 million but is likely to cost in excess of $2.5 billion. Contracts to build new houses were the highest on record just before each of the deadlines. The program is now closed to new applications and the recent extension relates only to the deadline for when construction needs to commence to receive the grant. The impact on GDP growth will be in future quarters and years because construction is valued on a work done basis.

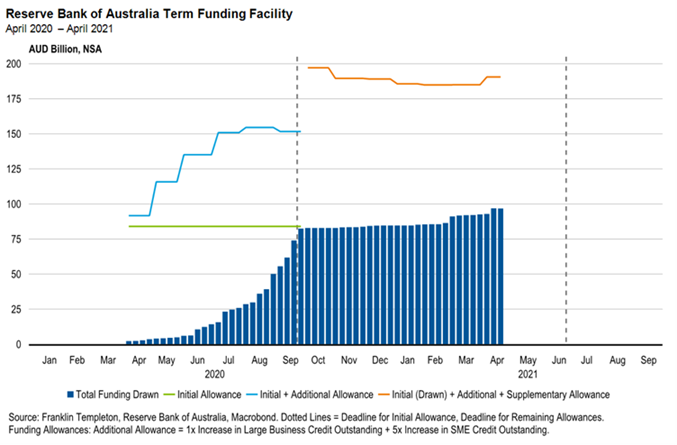

The Term Funding Facility (a monetary policy instrument) is scheduled to expire on 30th June 2021. Banks drew most of their initial allowance before it expired in September. In total banks can draw approx. $190 billion and we expect they utilise close to their full allowance because it lowers their weighted average cost of capital. There’s no direct impact on GDP growth but credit availability is higher.

What does all of this mean? Firstly it’s critical to have a deep understanding of growth and inflation. Macro tourists observing the headline statistics once per quarter rarely are able to translate their views into excess returns. We spend a lot of time dissecting the monetary and fiscal policies of Team Australia and thinking about this in the context of our leading indicators process. What we observe now is a large fiscal tightening as the government shifts the spending burden back to the private sector. The intention is good but the speed is too fast.

The stimulus afforded in 2020 offers a healthy tailwind via elevated household savings and a strong residential construction pipeline. But the risk is the government did too little. This is also what happened in the United States after the Global Financial Crisis. Fiscal stimulus was scaled back too early and monetary policy was left to do the heavy lifting – causing it to take more than 7 years from when the crisis ended to when the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) raised interest rates for the first time. This time the United States is being far more aggressive in its use of fiscal policy to support the economic recovery, but the same cannot be said about fiscal policy in Australia.

Monetary policy will need to do the heavy lifting from here. The question is what form this takes – the cash rate, yield curve control, or quantitative easing. The cash rate is at the effective lower bound and its very unlikely we see negative interest rates in Australia, so that leaves yield curve control and quantitative easing. The former targets the front end of the interest rate curve which is where households and businesses tend to borrow, while the latter targets the long end where the government borrows. With the spending burden shifting back to the private sector we believe it makes more sense to stimulate via yield curve control, which means extending yield curve control for at least another 6 months to the end of 2024. This decision would need to be announced by August. The current benchmark 3-year treasury bond is the ACGB April 2024 security, but come August this changes and the ACGB November 2024 security becomes the benchmark bond.

The current yield on the ACGB November 2024 bond is approx. 30 basis points but would move closer to 10 basis points if what we expect plays out. Why the large spread? We think because the market is considering stimulus on an ‘RBA-only’ basis, and translating recent good developments into nearer term rate increases. We believe it’s more likely the RBA stays on hold for 7 years vs. commences a tightening cycle in 2024.

More on the authors:

Joshua Rout, Portfolio Manager / Research Analyst, Fixed Income Franklin Templeton Investments

Andrew Canobi, Director, Franklin Templeton Fixed Income

Chris Siniakov, Managing Director, Franklin Templeton Fixed Income