Fertility rate set to rise, bond yields with it

Aging populations are putting strain on pension and health care systems and the Covid-19 pandemic, by causing people to delay births and pushing up the number of dependents, hasn’t helped. But new research from BCA Research predicts a rebound in fertility rates in the years ahead, though this could pressure bond yields higher.

The number of births collapsed during the pandemic in developed countries. While some evidence suggests that fertility rates are starting to recover, they remain well below the level necessary to maintain a stable population. This will remain a negative for stock markets over the longer term, according to BCA Research.

“On balance, we see demographic trends as being somewhat negative for stocks over the next one or-two decades,” said the BCA Research paper, The Coming Stork Wars.

“Aging populations are putting strain on pension and health care systems. The OECD expects the

old-age dependency ratio to double from 30 per cent to 60 per cent by 2075. Pension spending in the OECD is projected to rise by 1.4 per cent of GDP over the next 40 years,” says the report.

“Health care spending is likely to grow at an even faster pace. In the US, the Congressional

Budget Office sees federal government-financed health care spending rising from 5.7 per cent of GDP to 9.4 per cent of GDP by 2050.”

However, there is some good news. With the pandemic having run much of its course, global fertility rates may be bottoming and could rise significantly over the long run. While this trend would eventually benefit stocks, it is likely to come at the expense of higher bond yields, the report predicts.

“In the long run, faster population growth will lead to stronger corporate sales, which is a plus for equities,” said Peter Berezin, Chief Global Strategist with BCA Research.

“Over a shorter-term horizon, however, the global dependency ratio could end up increasing, as the number of retirees rises while the number of children that parents need to support goes up. This could put upward pressure on interest rates and bond yields. On balance, therefore, we see demographic trends as being somewhat negative for stocks over the next one or- two decades,” he said.

Fertility rates in Australia have long been in decline since the last years of the Baby Boom. From 3.55 babies per woman on average in 1961, fertility rates fell to around 1.74 babies per woman on average in 2018, according to official data. This trend has been driven by a combination of short and long-term factors: the age at which women have children has been increasing over time, and the total number of children per family has been falling over time.

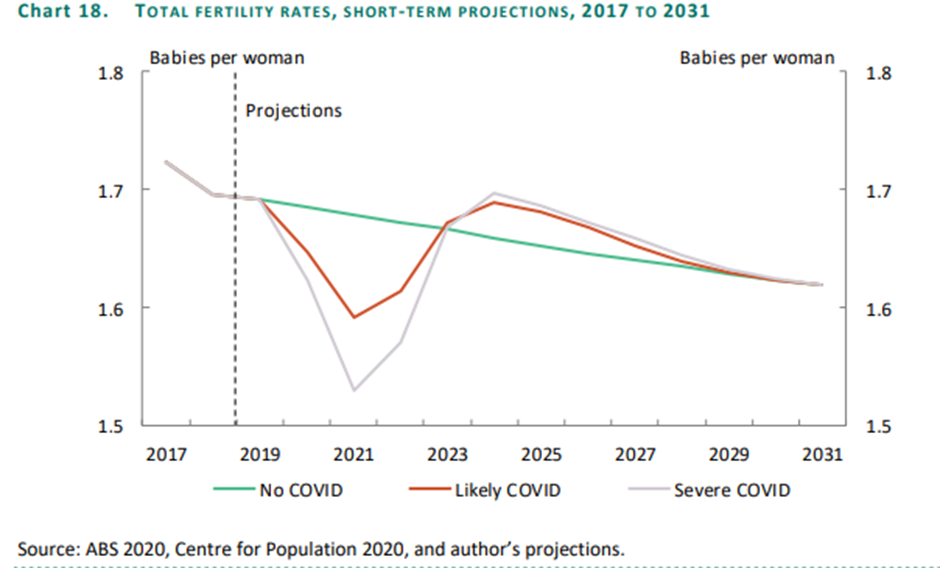

The Australian government has forecast that the fall in the fertility rate bottomed in 2021. This is shown in the graph below. While it is assumed that COVIDâ€19 has no effect on births in 2020, as almost all babies born in 2020 were from preâ€COVIDâ€19 pregnancies, the full impact of COVIDâ€19 on fertility was assumed to be felt in 2021 under two scenarios. In the ‘likely COVID’ scenario, the total fertility rate is assumed to be 0.15 babies per woman lower in 2021, and around 80 per cent of the babies that are deferred are assumed to be recuperated by 2032. In the ‘severe COVID’ scenario, the total fertility rate was assumed to be 0.25 babies per woman lower in 2021, and around 70 per cent of the babies that are deferred are assumed to be recuperated by 2032.

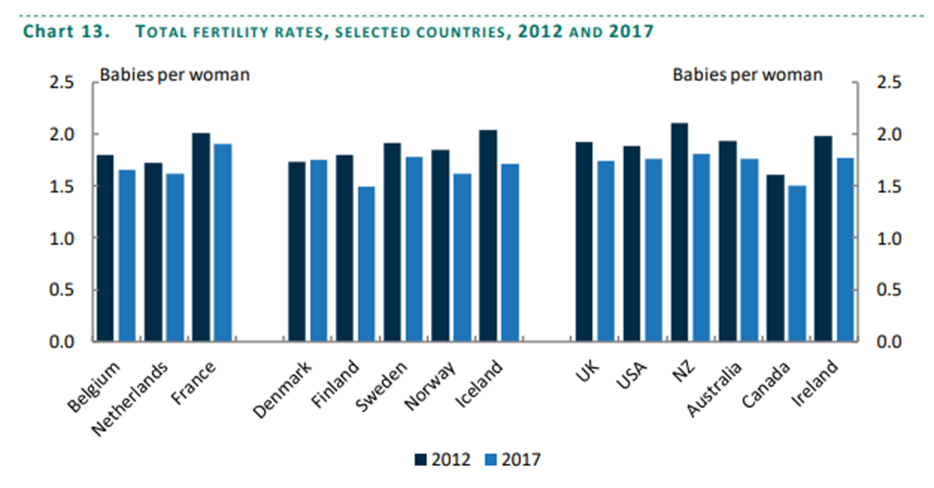

In recent years, the fertility rate has fallen in all moderately low fertility countries except Denmark and some of the falls have been substantial. For example, between 2012 and 2017, the Total Fertility Rate fell from 1.80 to 1.49 in Finland, from 1.85 to 1.62 in Norway, from 2.04 to 1.71 in Iceland, from 1.92 to 1.74 in the United Kingdom and, in New Zealand, from 2.04 in 2012 to 1.71 in 2018. By 2018, fertility in the US had fallen to 1.73.