Australian ‘green’ mining boom a pipeline dream as gas, coal funding soars

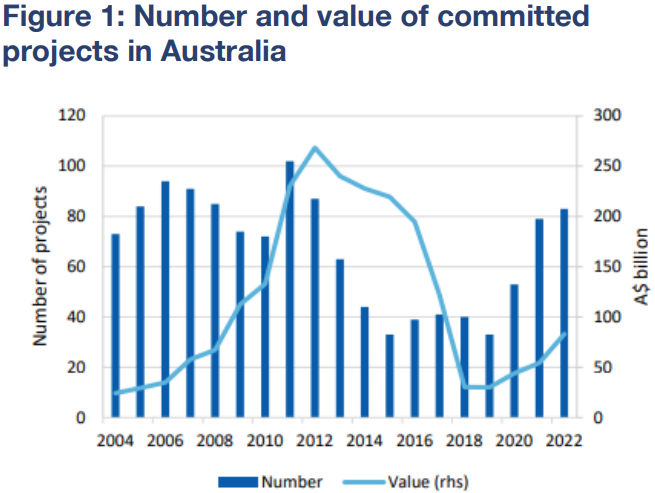

The value of committed mining and energy projects in Australia jumped 54 per cent to $83 billion in the year through October 2022 – topping 2008 levels reached in the lead-up to 2012’s peak. But about 64 per cent of committed investment is in gas and goal projects, dwarfing funding for renewable-energy projects, according to Vivek Dhar, mining and energy commodities strategist at Commonwealth Bank of Australia.

“If Australia is going to recreate the mining boom from the China-led super-cycle sometime this decade, it will need to become a major hydrogen exporter,” Dhar (pictured) said in a December 17 research note.

With the transition away from fossil fuels and adoption of green and renewable energy gaining traction as a global economic driver, the commodities that will power decarbonisation – such as copper, nickel, hydrogen and lithium – are becoming increasingly important to the global economy. The growing demand has prompted hopes for a local boom akin to the 1996-2016 commodities super-cycle, led by growth in China, that saw the 2012 peak in Australian mining and energy investment at more than $250 billion.

But, according to Dhar, those hopes are premature, and the characteristics of a super-cycle do not exist for green energy. “The evidence does not yet point to the start of a ‘green’ mining super-cycle whereby significant investment is taking place in the commodities needed in the energy transition,” he said.

“The outlook suggests Australia is unlikely to experience a mining boom anywhere near the scale of the China-led super-cycle in coming years just from the metals (i.e., lithium, copper, nickel, cobalt, graphite and rare earths) needed in the energy transition.”

Lithium a standout in green energy opportunities

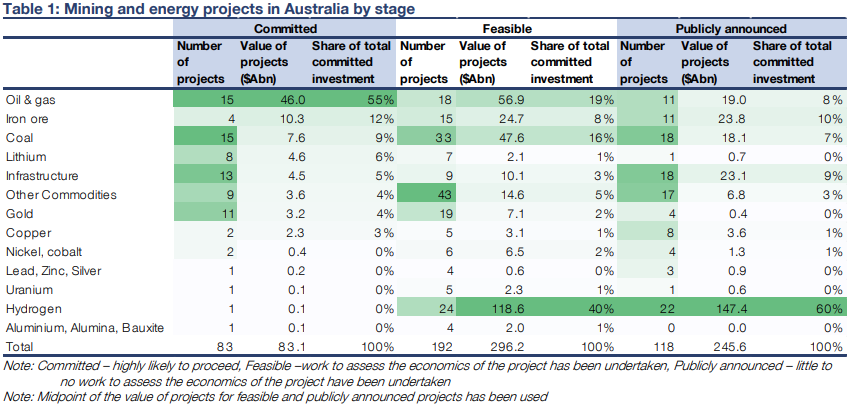

After oil and gas, iron ore, and coal projects take out the top 77 per cent of committed investment in the picture for the year through October 2022, the next highest share – at 6 per cent – goes to lithium, a key input in batteries needed to decarbonise the power and transport sectors, according to the CBA research, which cites data from the Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources (DISER). Projects around infrastructure, “other commodities,” gold and copper account for the rest of the year’s committed investments.

Calling lithium the “most promising metal amongst those needed in the energy transition that is attracting investment dollars” – there is also a handful of copper, nickel, cobalt and other projects in the pipeline, but they represent zero share of committed investment – Dhar noted that despite the small investment share allocated to lithium domestically, Australia accounted for about 55 per cent of global lithium output in 2021.

Hydrogen, meanwhile, is among the zero-investment-share cohort of green energy projects in 2022, with just one project currently at the “committed” stage, according to the DISER data. But the outlook here is particularly bright, with hydrogen projects accounting for 40 per cent of the value of “feasible” projects and 60 per cent of “publicly announced” projects, or those preceding the “committed” stage.

“Virtually all projects in the pipeline use renewable power to generate hydrogen from water,” known as “green” hydrogen, Dhar explained. He also cited two “megaprojects” in Western Australia that account for more than half the value of pipeline hydrogen projects and “are designed to make Australia a hydrogen exporting superpower”.

However, Dhar cautioned that, “at this stage, government support is still necessary to support the supply and demand of hydrogen in Australia”.

Downstream processing also represents opportunity for investment and growth, based on the continued domination of the Australian pipeline by upstream projects, but Dhar noted that “high labour costs and now higher energy costs reduce the competitiveness of Australia becoming a major player in downstream industries”.

Moreover, high-emitting downstream processors are facing challenges in the form of stricter carbon compliance standards from July 1, when the federal government’s new Safeguard Mechanism rules take effect.

And global policy shifts represent another headwind to the development of downstream processing capabilities in Australia, with the game-changing US Inflation Reduction Act and European incentives making the US and EU prime destinations for downstream processing facilities as they seek to shore up their self-reliance and supply chains.

“For Australia to now develop significant downstream processing, state and federal governments would need to provide supportive policies in line with or in excess of what Europe and the US are providing,” Dhar wrote.

Traditional commodities also challenged

Australia may be underinvested for a boom in green energy and mining, but the global trend is still toward decarbonisation and the decreasing role of traditional energy sources, and gas and coal are facing their own structural challenges as the world’s energy needs transform. The war in Ukraine has exacerbated many of these challenges and brought energy security to the fore.

Complicating the short-term outlook for gas markets in Australia is the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission’s introduction in December of a temporary price cap of $12 per gigajoule for gas sold to domestic wholesale customers.

The Gas Market Emergency Price Order, which the federal government says will curb soaring energy bills while supporting the gas industry, applies only to uncontracted supply and does not affect exports.

A similar price cap was also introduced for coal, setting a price ceiling of $125 per tonne. Producers say the caps will only exacerbate affordability concerns.

After the ACCC issued new guidelines January 17 to clarify how it will enforce the gas cap – including by issuing penalties of up to $50 million, three times the value of the benefit obtained, or 30 per cent of turnover for the offending period, whichever is greater – the Australian Petroleum Production and Exploration Association said the new guidelines “do little to resolve the short and long-term uncertainties in the market” and leave too much to the discretion of the ACCC.

“The interim guidelines reinforce the disconnect between the policy and the operations of the Australian gas market in practice,” APPEA chief executive Samantha McCulloch said. “It is clear that the new rules will make it extremely challenging for producers to continue to provide the flexibility of gas supply required by customers.”