Pandemic exposes folly of macro

It has been a difficult few years, or perhaps decades, for forecasters of all kinds. Whether it was election polling that failed to predict both Trump’s and Morrison’s stunning wins, or the UK’s Brexit; spiralling coronavirus case numbers; or those calling for massive property market and economic pain throughout 2020, the end result was the same. Ultimately, these expert forecasters failed to predict anything near the actual events that occurred, despite their best efforts.

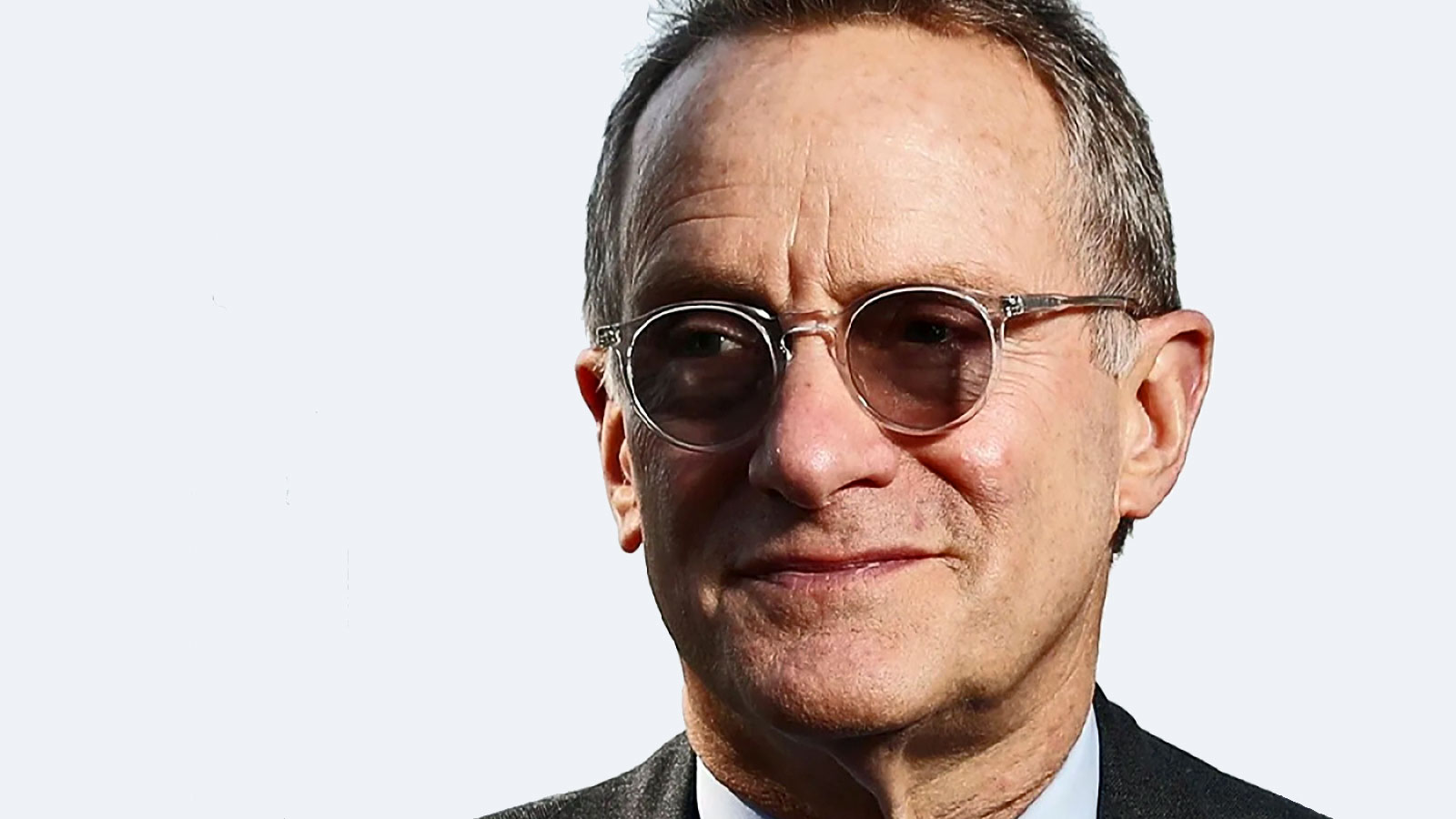

Warren Buffett is widely quoted as saying “forecasts may tell you a great deal about the forecaster; they tell you nothing about the future” and the proof isn’t hard to find. Reading the latest missive from investment doyen Howard Marks of Oaktree Capital, titled Thinking about macro, offered some even clearer evidence.

According to an internal analysis, the median of analysts’ forecasts for the S&P500 in each year since 2000 missed the actual result by an average of 12.9 percentage points. More amazingly, the average return throughout this period was just 6%, evidencing the scale of the miss. More recent events reflect an even bigger difficulty in understanding the environment we now operate in, with December 2019 forecasts for the market suggesting it would rise by 2.7%.

No doubt many will say that no-one saw the pandemic coming, yet even in April 2020, once the Federal Reserve had stepped in, this was reduced to minus 11%. What was the actual result? 18.4%, meaning the initial estimate missed by 16 percentage points, and the subsequent adjusted forecast an incredible 30 percentage points off! As the author suggests, this is like predicting sunshine every day in a city that sees rain 30% of the time. The story is broadly similar in Australia, Europe and pretty much everywhere else, for that matter.

Yet a day doesn’t pass without another economist predicting an upcoming economic announcement with near-certainty, or in the worst case, a market pundit predicting some sort of disastrous event that never eventuates. According to Marks, “hundreds or perhaps thousands of people make their living as professional market forecasters, despite the fact that the median forecast is of no value, wrong on average, positive in good years and bad,” and finally, the most inaccurate when it would have been the most profitable; that is, when markets fall but all are predicting markets to gain.

The result is that one of Oaktree’s key investment rules is never to invest based on a macroeconomic forecast. I agree wholeheartedly with this view. Every conference, presentation or fund manager pitch starts with a view on the macro economy, whether it is interest rates, inflation, or GDP growth, something that Marks suggest “simply isn’t knowable.”

‘”An economist is a portfolio manager who never marks-to-market” is a lesson Marks received from an unnamed mentor. He highlights that no economist prefaces their presentation with their track record of how often they have been right or wrong in the past, which is the very information we demand from every investment manager we employ. Perhaps as an industry it is up to us to demand this from those who are making some of the most important calls on a day-to-day basis.

In 2021, Australian economists are paraded as celebrities, delivering keynote presentations and performing on news bulletins, all the while seemingly failing to predict anything accurately, or more importantly, to drift far from consensus. More interesting is the fact that even if they are right, the ability to add value is questionable at best.

“Consensus forecasts provide no advantage,” says Marks, with only those able to be more right than others consistently able to dependably deliver above average returns. Such people are, of course, needles in haystacks. So, why then do we continue to spend an inordinate amount of time on such an unimportant part of the investment process?