Everyone is losing their mind over the wrong inflation signals

Everyone is losing their minds over inflation signals that don’t matter.

It is hard to pick up a paper or piece of market commentary at the moment that doesn’t point to some piece of ‘evidence’ that inflation is here and roaring. We have been doing a lot of reading recently around the topic in the context of the ‘great inflation’ between 1965-1982.

It is called the great inflation because CPI in most developed markets averaged high single digits and into the teens for an extended period. It’s also called inflation because the `~1-2.5 per cent experience this century for most CPI measures isn’t inflation. That’s stable prices.

Central Banks target price stability which is usually characterized as ~1-3 per cent depending on where you are – i.e. stable prices as defined by something a little above zero (they don’t want deflation) but not too high (they don’t want excessive price rises). So, call around 2 per cent is the happy medium. The great inflation was so significant it led to the era of inflation targeting by central banks, led by New Zealand who adopted this framework in 1989.

In 1964, US CPI was 1 per cent and the Fed was relaxed. By 1966, it was 4 per cent, 1970 6.2 per cent and then of course it surged into the double digits over the next 10 years. Inflation like a thief in the night appeared. The fascinating aspect of this period is that economists and academics are still arguing today about what exactly caused it.

The Scottish writer and philosopher Thomas Carlyle didn’t call economics the dismal science for nothing.

Of late, we find people going into apoplexy over all sorts of price rises which are almost by definition one-off and not really evidence of true ‘inflation’.

Such as

US Used Car Prices

Or

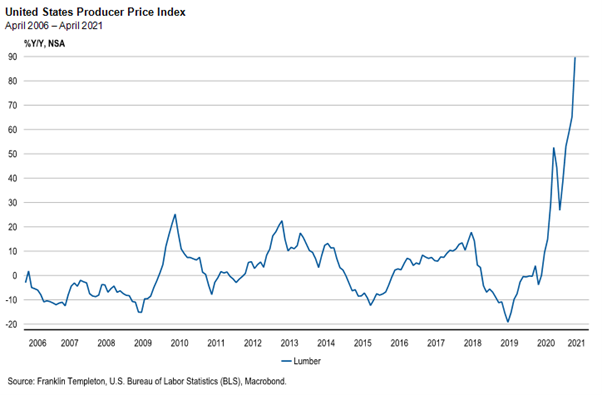

Lumber Prices

Or

New Zealand House Prices

In almost all cases, these are examples of one-off shocks caused by COVID related (temporary) supply shortages and surging demand from economies being re-opened and flush with stimulus. Both will fade as the year progresses.

The bond market is of course dismissing these factors which aren’t evidential of inflation pressures. Hence both US and Australian 10-year yields continue to look like they’ve posted a top for now.

Is inflation coming? As we have said before, yes, insofar as this decade almost certainly ushers in such a period. But we aren’t there yet and probably won’t be for several years. At a minimum, much lower unemployment and much higher wages growth will be more consistent with such inflation.

It is too simplistic to point to some conditions as being proof that inflation is here and is structural:

- Easy monetary policy? Maybe but we’ve had that for a long time. No inflation.

- Easy fiscal policy? Maybe but Japan has had that for decades. No inflation.

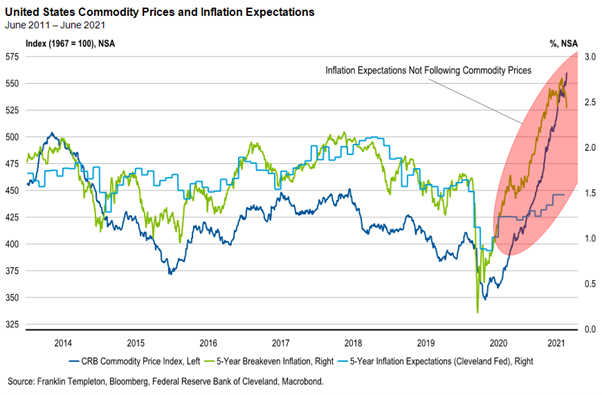

- Strong commodity prices? Maybe but oil was north of $100 between 2010 and 2014 and CPI stayed low.

- Huge money supply growth? Maybe but US M2 growth went 5x from 2010 to 2012 and no inflation.

In humility, given no one can agree on what caused the great inflation, it seems unlikely that the presence of any one or more of the above factors will give the ‘Aha’ moment either. The reality is, just like from 1964-1965, inflation will just appear like the genie in Aladdin.

One thing that will almost certainly point to its arrival, however, is a rise in inflation expectations. Despite the move higher in breakeven inflation and commodity prices, these haven’t really moved. Which informs our ‘not yet’ view. Until we see a broad surge in expectations, the inflation genie stays in the bottle.

In fact, breakeven inflation rates (market implied inflation – the difference between nominal and real bond yields) has started to decline of late.

By: Andrew Canobi, Director, Franklin Templeton Fixed Income

Joshua Rout, CFA Portfolio Manager / Research Analyst, Fixed Income

Franklin Templeton Investments

Chris Siniakov Managing Director, Franklin Templeton Fixed Income