Is this the biggest risk in your portfolio?

While listening to a conference by multi-asset investment manager, Ruffer LLP – an event we covered here – it became evident that most portfolios are inadequately prepared for the future that lies ahead. While UK-based Ruffer is little-known in Australia, the group manages over GBP$21 billion ($37.5 billion) across most asset classes, and recently received significant press after adding an exposure to Bitcoin to its core fund.

However, it wasn’t Ruffer’s view on Bitcoin that piqued my interest, rather it was an innocuous slide that measured the correlation benefits of holding traditional government bonds at current valuations. Before moving into the specifics, it is important to understand the background, being that almost all capital invested around the world is managed using a traditional ‘balanced’ approach. Under this approach, which is grounded in academic research, an allocation to low-risk government bonds is always appropriate for portfolios and can be as high as 40 per cent of the amount invested, with equities tending to make up the remaining 60 per cent.

The premise of this allocation to government bonds is that they offer (or once offered) three benefits to investors: consistent income, capital stability and correlation benefits. At this point, the focus is on the latter, which has become increasingly important in an environment where calls of equity market bubbles lead almost every news headline. Historically, with March 2020 a perfect example, when equities markets fall significantly, by say 10 per cent, the lower-risk government bond portion outperforms, offsetting the loss of value in the equity component. This is due to the “flight to safety,” with greater demand for a limited amount of bonds sending their prices higher.

Today, according to Ruffer, there is little room left to move. Quantitative easing and so-called money-printing policies have fixed short-term interest rates near zero, with central bank buying of government bonds doing the same for the 10-year bonds as it has for short-term rates. The basic relationship between bond values and rates is simple: as interest rates fall, existing bonds become more valuable because they yield more. It should be no surprise then that government bond yields have never been lower, and as a result their valuations have never been higher.

Are correlation benefits extinct?

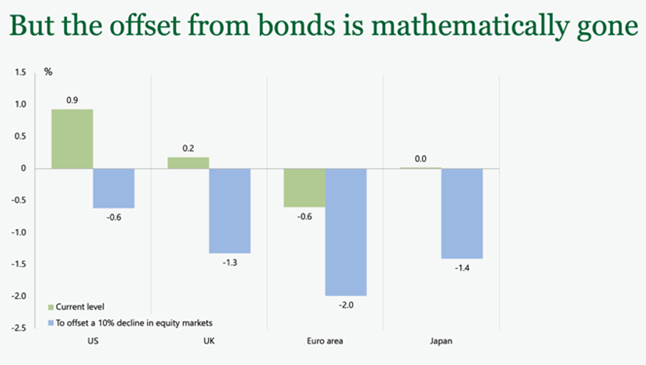

The slide included below shows how the simple relationship between bonds and equities has clearly been broken. The chart shows the resultant fall in bond yields that would be required to offset the negative impact of a 10 per cent fall in equity market indices. As it stands at the beginning of 2021, the yield on US government bonds would need to fall from 0.9 per cent today to negative 0.6 per cent. It doesn’t get much better in Europe, with the yield needing to fall from negative 0.6 per cent to negative 2.0 per cent.

If it were not clear before seeing this slide, it must be now. Retaining a significant exposure to traditional, long-duration government bonds is effectively betting that they will protect your portfolio in the event of another sell-off. This is because they offer little in the way of income and therefore would only be included on the basis of their expected correlation benefits. Yet to offer any correlation benefits they must fall further into negative-yielding territory; this is clearly speculation, not sound portfolio management strategy.

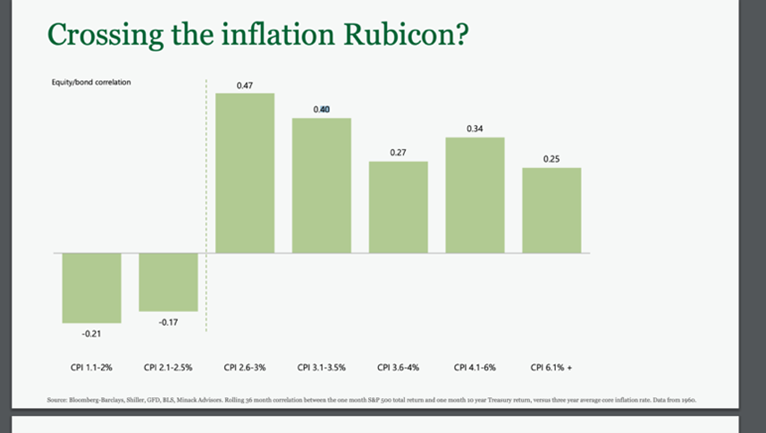

Doubling-down on this concept, Ruffer also provided a slide showing the evolving levels of correlation between equities and bonds. While many asset allocation models are based on static correlation levels, the real world is a far more complicated place. According to Ruffer, should central bankers around the world be successful in generating inflation of between 2.5 per cent-3.0 per cent, the correlation between equities and bonds would actually turn positive, meaning you could lose money on both.

While the calls of a great year for markets grow louder, now is clearly not the time to be sticking with the status quo.