Taking back control?

This analysis was undertaken in autumn 2021, long before Russia’s latest invasion of Ukraine.

There remains an intense debate about the economic consequences of Russia’s military incursion. But there is surely no way to know how severe and long-lasting the constraints on global commodity supply will be and so no credible way to quantify the shock to global growth, inflation and investor sentiment.

Instead, we ask: will Russian President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine undermine or reinforce the change in inflation regime, the most important consideration for any long-term investor?

The answer to us is clear. President Putin’s actions have added significantly to the inflationary shock unleashed by the pandemic – a shock striking an already inflation-prone system. Whatever course Putin chooses to take from here, the difficulties facing central banks are even more acute than they might otherwise have been. Inflationary pressures, the likes of which the world has not seen in four decades, are buffeting an inflation-intolerant financial system which has become hardwired both to the absence of inflation risk and to its close cousin, ‘low for long’ interest rates.

The Federal Reserve will have to slam on the brakes harder than it had originally envisaged; other central banks will have to start normalising policy in 2022, when once they might have dithered. Whether the mechanism is direct (via the hit to real incomes from higher energy and food prices) or indirect (via the enforced tightening of financial conditions), the likelihood of a global recession in the next 12 to18 months has jumped. Investors are unprepared not just for a recession but, critically, for one where inflation could remain stubbornly high and central bank support may be slower to arrive.

DEMISE OF THE DEFLATION MACHINE

In the late 1970s, the world was on the cusp of radical change. The ‘Deflation Machine’ was being born. Deng Xiaoping began reforming China’s moribund economy. In the West, liberal, free-market ideals were gaining traction, ideals that underpinned the subsequent regime of rapid, disinflationary global growth.

A global financial crisis and pandemic-induced economic heart attack later, this regime is in its dying days. No one knows exactly what will follow, but the broad outline is becoming clear. At its core will be ‘strategic rivalry’ between the US and China.1 Domestically, politics will become less internationalist, tolerant and laissez-faire and more nationalist, parochial and interventionist. Globally, inflation is likely to be higher and more volatile. Inflation risk, an absent adversary throughout the careers of most investors today, will need to be priced once again. Its return will have profound consequences for prospective asset returns and cross-asset dynamics.

THE PARADOX OF DEBT-INDUCED INFLATION

For many, the idea that we are entering a new regime of long-term high inflation is outlandish, given excessive private and public debt. Surely debt overhangs are deflationary. We don’t think so. In fact, debt burdens that will be unmanageable at historically normal levels of interest rates are necessary for the coming regime change.

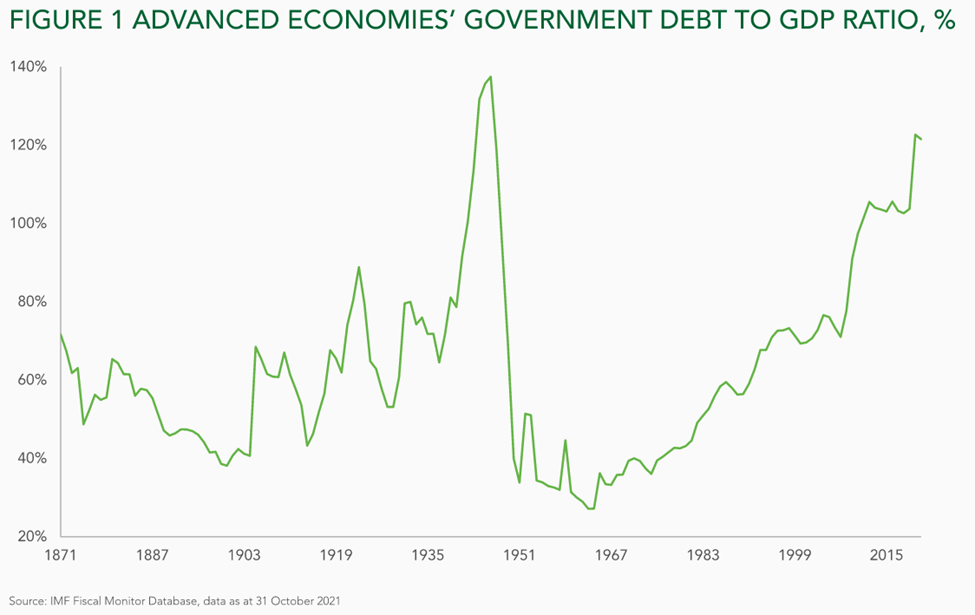

The long tail of vulnerable borrowers, including many governments (Figure 1), has fundamentally reshaped how policymakers react to economic shocks. Our debt-heavy, hyper-financialised economy can cope with neither another financial shock nor a material rise in (real) interest rates. Our political system, meanwhile, is in no shape to accommodate more economic hardship on Main Street. A bout of inflation may now be the only politically acceptable route out of the rabbit hole down which two decades of loose monetary policy and credit excesses have taken us.

KNOWN DESTINATION, UNCERTAIN JOURNEY…

We remain convinced that a phase of more persistent and malign inflationary pressures has begun, but the possible paths ahead remain unclear. One involves a direct route to our inflationary destination; the other meanders first through financial disruption and (apparent) deflationary dangers. We have, therefore, built a portfolio robust to both ‘left-tail’ and ‘right-tail’ outcomes. A market comprising richly priced assets – justified by structurally low risk-free discount rates – is fragile. In the next one or two years, it may unravel because of either ‘left tail’ threats to earnings, liquidity-fuelled markets and the economy or ‘right tail’ dangers to the nominal risk-free discount rate.

If inflation in advanced economies persists above the 2% parapet, central banks will have to decide between two unpalatable courses of action. Do they stick with their run-it-hot strategy out of concern for financial stability and a broad and inclusive labour market recovery? Or do they revert to a more traditional policy approach, getting ‘ahead of the curve’, but running the risk of a policy-induced recession? In the first of these scenarios, we could enter the high and volatile inflation regime in one fell swoop. In the second, central bankers might ensure a soft landing, with asset prices deflating just enough to restrain emergent inflationary momentum, without a recession. But history suggests such an outcome is highly improbable.

A bout of inflation may now be the only politically acceptable route out of the rabbit hole down which two decades of loose monetary policy and credit excesses have taken us.

TRAPPED DOWN THE MONETARY RABBIT HOLE?

It is tempting to believe that, if we are diverted down the path of financial disruption by aggressive central bank tightening in 2022 and 2023, we will not arrive at our inflationary destination but instead at the ‘secular stagnation’ status quo ante.

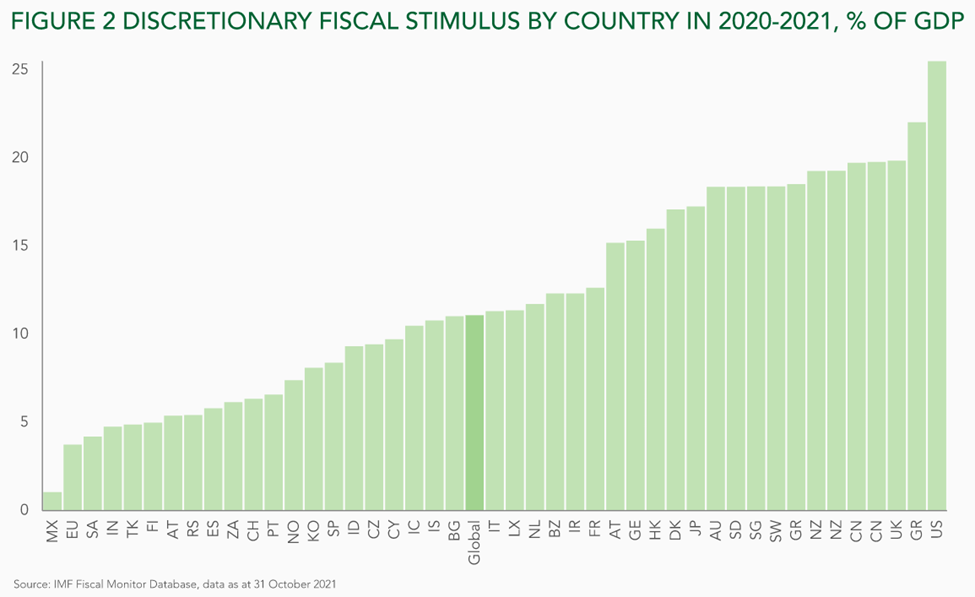

There are three reasons to be sceptical. First, despite a massive pandemic-induced spike in inflation and the fastest rebound out of recession in post war history, to date we have seen only a paltry reduction in policy stimulus, itself the most aggressive and wide-ranging stimulus programme in peacetime history (Figure 2). So, when they next stare into a recession, central bankers will find their armoury even more depleted than was the case in early 2020. Whether made explicit or not, ‘helicopter money’ will then be the most palatable and effective tool.

The second reason relates to the economic legacy of the pandemic. People are buying different things in different ways, working in different places, using different modes of transport and living in different locations. The resulting supply side disruption will make calibrating any future policy response to financially driven economic weakness that much trickier.

The second reason relates to the economic legacy of the pandemic. People are buying different things in different ways, working in different places, using different modes of transport and living in different locations. The resulting supply side disruption will make calibrating any future policy response to financially driven economic weakness that much trickier.

The third reason is the most convincing to us. Policy interventions in the years after the Lehman collapse focused on Wall Street, not Main Street. The pandemic has revealed that sizeable and broad-based support for Main Street is the only choice voters will tolerate from their representatives. As politicians responding to the costs of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine are now discovering. this is consequential because support for Main Street can lift inflation, where stimulus aimed at Wall Street cannot.

NOT A REPEAT OF THE 1970S

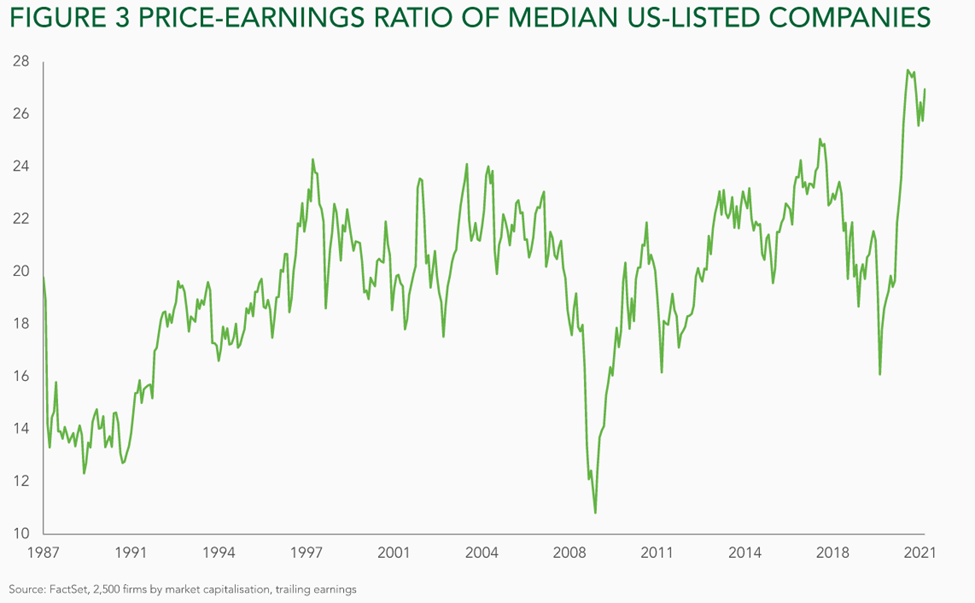

The coming phase of high and volatile inflation probably won’t look like the 1970s. The starting point is more extreme in two critical ways. First, the financial ecosystem has become primed for a world without inflation risk. Risk-free interest rates, the anchor of today’s fiat system, are at multi-century lows.2 Richly priced risky assets (Figure 3) are justified, primarily, on the basis that these depressed risk-free interest rates will endure. Similarly, mean-variance investing (via balanced ’60-40′ portfolios) dominates today’s investment landscape, because government bonds are seen as a low volatility ‘safe asset’ that protects portfolios during equity market drawdowns.

The second consideration is overtly political. Life was immeasurably better in 1970 than it had been in 1945. Wealth and income inequality were as low as they had ever been. Today, the backdrop is very different. The average household’s real income has been stagnant (or worse) for over a decade in most Western societies. Wealth and income inequality are both much higher than five decades ago. And a second Cold War is underway, with far more serious ramifications for the global economic system.

We are not building a portfolio with the expectation that average inflation, or its peak, will match that seen five decades ago. We are troubled by something that is historically far more mundane, but of which most investors today have no experience. In the transition to this new regime, there is much we are still uncertain about. Crucially, how far will central bankers go to contain inflationary pressures? The answer to that question will determine what the scenery looks like on the way ahead.

JAMIE DANNHAUSER

Economist